Beyond Status Quo: Dekleva Gregoric Architects' Tina Gregoric on Local Specificity, Critical Thinking, and Instigating Joy

Tina Gregoric by Tadej Znidarcic.

By Julia Gamolina

As a practicing architect and professor, Tina Gregoric strategically intertwines research and practice of architecture to address the current social and climate challenges. Her firm, Dekleva Gregoric Architects, has been awarded projects that span diverse contexts in the EU and USA, ranging from affordable housing to open public space transformation. Her research topics include nanotourism, material and circular design strategies, and social interaction.

JG: You practice and teach between Slovenia and Austria. What have you been most focused on, both with your practice and your teaching, in 2025?

TG: Holding a professorship in Vienna while co-leading our Ljubljana-based practice offers a unique opportunity to explore critical issues from the perspectives of two Central European cities, rich with shared history spanning centuries yet marked by notable differences. My department at Vienna University of Technology pursues several research areas: resilience typologies, bioregional design, adaptive reuse, healthcare architecture, and regenerative tourism.

In 2025, my intensive research and teaching have primarily concentrated on materiality through a bioregional approach. For centuries, explicit materiality has defined the identity of cities, towns, and villages worldwide — stone houses in Mediterranean towns and brick structures in Central and Northern Europe for example. Local materials narrate layers of local history and geology, fostering a sense of identity among residents. Along with our students and emerging international creatives in the LINA European Architecture Platform, we are exploring ways to address the climate crisis by emphasizing local resources instead of relying on extractive materials with extensive transportation. Ecology and materiality—deeply connected to people and communities—have been central to our practice for over two decades.

In terms of practice, 2025 provided an opportunity to document and reflect on two recently finished homes, both perched on the forest edge with sweeping views, where we examined the potential for eco-friendly wooden construction, both in Europe and the USA. A pair of dark wooden vacation homes in the Julian Alps blends seamlessly into the surrounding trees, while the light interior intentionally reveals the innovative, highly ecological structural Dowel Laminated Timber (DLT). A retreat on the Pacific Northwest coast, Discovery Bay House, explores a grid of visible local timber frame structure, creating an immersive experience with nature.

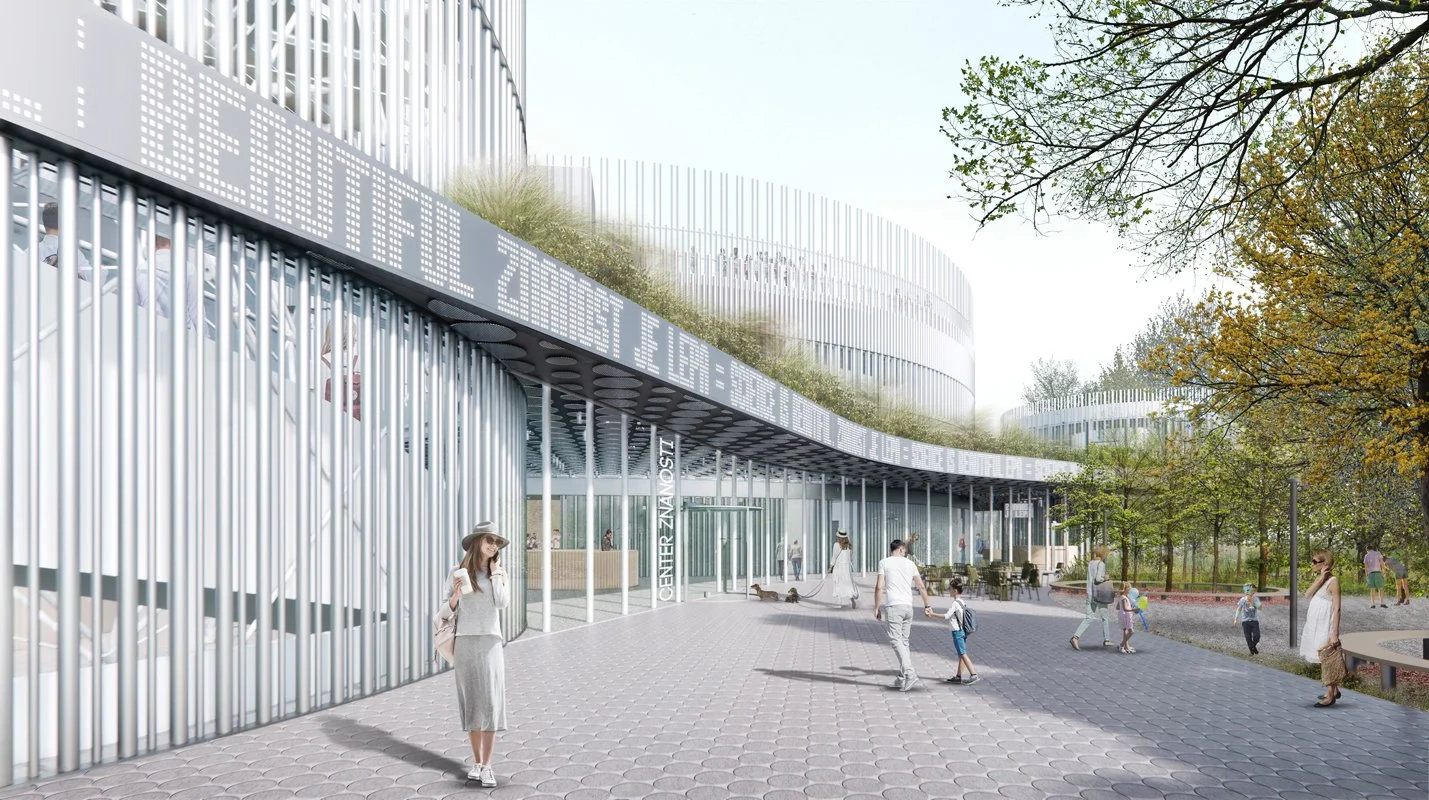

Science Centre Ljubljana. Visualization by Dekleva Gregoric Architects.

Slovenian Pavilion for EXPO Osaka 2025. Visualization by Dekleva Gregoric Architects.

Now let's go back a little bit — why did you study architecture? How did your studies differ in Ljubljana and London?

For a long time, I believed I would become a scientist. In high school, I was interested in mathematics, comparative literature, philosophy, and art history. Besides critical thinking and ambition to improve our planet and community, I realized that what I truly wanted in life was to create—to see and touch the results of my work. I didn’t want my work to be measured in hours, numbers, or reports. Through a rigorous entrance exam, I enrolled in a five-year cohesive architectural program in Ljubljana.

Ljubljana was a remarkably optimistic tiny capital of the newly formed Slovenia — a fifteen-minute city characterized by walking and biking. It is and was a unique city to live and study architecture because the sheer density of extraordinary interventions by Jože Plečnik and his contextual modernist contemporaries creates such a rich layer that it consciously and unconsciously teaches you daily, shaping values and perspectives you carry forward: explicit materiality, inventiveness within scarcity, importance of local specificity, and the creative take on heritage.

In addition to our studies, I participated in several open competitions, and the award me and my colleague received in the highly competitive UIA ‘96 international competition in my third year gave me extra ambition. Aljosa had already started his first studio and begun building his initial works, while I was researching and advocating for the preservation of extraordinary modernist architectural heritage in Slovenia. In 2000, immediately after graduating, we both decided to enroll in the AA DRL postgraduate program at the Architectural Association. To our positive surprise, the AA proved to be more than just a place for experimenting with digital design tools; it was an open, independent space for a wide range of perspectives. We appreciated collaborations with philosophers, historians, structural engineers, and responses from the then-leading practitioners. The AA's extreme internationalism was further extended through an exchange programme between the EU and the US, which led me to a workshop at Princeton.

“Local materials narrate layers of local history and geology, fostering a sense of identity among residents...we are exploring ways to address the climate crisis by emphasizing local resources instead of relying on extractive materials with extensive transportation.”

Tell me about your experiences working for various offices before starting your own practice. What did you learn that you still apply today?

My experience working with other architects in their respective offices was minimal, probably intentionally, because there was an inherent ambition to return from London to Ljubljana and start a practice with Aljoša as soon as possible. However, as a student, I spent a few weeks interning with a team competing in an open competition at the progressive young firm Njiric&Njiric in Zagreb. Additionally, after graduating from the AA DRL, we were invited to Zaha Hadid's studio to join a team for a major international competition—the BMW factory in Leipzig—which we ultimately won. Zaha Hadid Architects was a medium-sized practice at that time, and although brief, it was a very unique and intense experience.

Zaha was an immense thinker, an extremely intelligent woman. She was also very funny and very critical. We met her as students when she was a juror at our project presentations, and we saw how she thought. She was the most penetrating critic, finding a weak point instantly. She could see student projects for what they truly were, not for how they related to her own work. In fact, this should be a trait of every professor who does not want to create followers but aims to promote critical thinking. I mainly learned from both principals, Hrvoje Njiric and Zaha Hadid, that teaching alongside practice can foster a continuous critical edge within the discipline.

How have you personally evolved in your years with your practice and teaching? How did you expand your skill set, what have you learned, all that.

I've become more effective at communicating with clients and understanding their needs and preferences, even when they're not directly expressed. Our practice also needed to quickly expand our skills in Building Information Modeling (BIM) to cover all phases of our latest, very exciting public project, the Science Centre, which is still under construction.

As a professor, I mainly needed to learn how to indirectly teach and coordinate architectural design for a specific course with a large team of instructors. Self-critical reflection enables me and my team to access and improve various methodologies and course formats. I still greatly enjoy teaching across different years, but it is especially meaningful to actively exchange ideas and challenge my diploma students.

University Campus Livade 1.0. Photography by Miran Kambič.

Looking back at it all, what have been the biggest challenges? How did you both manage through perceived disappointments or setbacks?

A continuous challenge is maintaining our studio structure—large enough to lead the design of major public projects, yet small enough to remain agile and selective about the projects and clients we believe we can collaborate with at the highest level. We were extremely fortunate at the start of our practice, managing to win several open competitions, from affordable housing and university campuses to a large masterplan for mixed-use development.

The challenge came when we realized that winning an open public competition does not necessarily guarantee that the studio will develop or build the project, as politics and the overall economy impact investments, whether public or private. Recently, we faced a significant setback when the government decided not to build our winning proposal for the Expo Pavilion of Slovenia in Osaka, Japan, citing increased expenses for major flood relief. We immediately shifted gears and participated in the competition for single-family houses for those who lost their homes during these floods and later submitted the Expo Pavilion of Slovenia for the Unbuilt Award, which we were honored to receive.

Who are you admiring now and why?

For decades, I was intrigued by Alison and Peter Smithson for their intellectual positions and multi-modal understanding of architectural practice. They deliberately treated creating books as an equal endeavor to designing an architectural project. Their experimental editorial work is matched by an experimental approach to the transformation of the existing, or rethinking of the urban fabric. They were activist and provocateurs who challenged and connected with other architects to address the then status quo.

“...don’t regret the time spent on a project that stopped for whatever reason. All of your efforts are cumulative.”

What is the impact you’d like to have on the world? What is your core mission? And, what does success in that look like to you?

I’d like to improve the status quo in our communities and environment, both spatially, socially, and environmentally, and always also on a material and aesthetic level. This involves improving the everyday quality of life for many people by defining their homes, neighborhoods, and their connections among themselves and with their immediate surroundings. We like to surprise with the unexpected and instigate joy.

Our core mission is also to share knowledge across disciplines and with the wider public through exchange, open source projects, designing single-family houses for those who can’t afford an architect (XH SYSTEM HOUSE), or to intensely develop and promote NANOTOURISM as a creative critique of the current environmental, social, and economic downsides of overtourism, as a participatory, locally oriented, bottom-up alternative.

Twin Alpine Houses. Photography by Ana Skobe.

Finally, what advice do you have for those starting their careers? Would your advice differ for women?

Be proactive in your own community — on your street, in your town. Approach both clients and the public in both public and private settings. Don’t wait for someone else to discover your skills and expertise. Work in diverse conditions and environments. Partner with others. Open up many paths. And, don’t regret the time spent on a project that stopped for whatever reason. All of your efforts are cumulative.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.