Curating Perspectives: Beatrice Galilee of The World Around on the Ever-Evolving World of Architectural Curation and its Impact in a Post-Pandemic World

Beatrice by Noam Galai.

By Patrick Dimond

Beatrice Galilee is a London-born curator, writer, and cultural advisor who is internationally recognized for her expertise in global contemporary architecture and design. She is the author of Radical Architecture of the Future, published by Phaidon in 2021, and from 2014-2019 served as the first curator of contemporary architecture and design at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Currently living in New York, Ms. Galilee is co-founder and executive director of The World Around, a new platform for contemporary design and architecture that is in residence at the Guggenheim Museum. Beatrice is a visiting professor at Pratt Institute, where she lectures on curating.

Beatrice Galilee served as chief curator of the 2013 Lisbon Architecture Triennale, co-curator of the 2011 Gwangju Design Biennale, and co-curator of the 2009 Shenzhen Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism. Between 2010-2012 she launched and co-directed The Gopher Hole, an experimental exhibition and project space in London. Between 2006-2009 she served as the award-winning architecture editor of Icon Magazine, one of Europe’s leading publications in architecture and design, and is a respected critic: her reviews, profiles, and features on contemporary design have been published in several international magazines and books as well as daily newspapers.

PD: Tell me about yourself and your foundational years. Where did you grow up, and what did you do as a kid?

BG: I grew up in southwest London in the 1980s. My father and I lived together in a small apartment, but I was raised with and by a family of aunts, uncles, and cousins all living just minutes away from us. During my foundational years, I spent a lot of time alone reading, writing, and drawing. My primary studies in England were maths and further maths because of my father, art because of my mother, and history through my aunt and uncle, who taught me so much about how the world works. So, while a bit unusual as the only child of a single dad, my formative years were quiet, happy, and peaceful. I attribute that to having come from a family of teachers. The idea of pursuing architecture as a discipline first came about because of my mother who I think saw architecture as a convening of all my interests and curiosities.

What about curation? Were there curators or collectors in the family?

Professionally, just teachers. My grandfather was a teacher. My dad was a teacher. My aunts and uncles and cousins are all teachers. [laugh]. But in terms of love for culture, I was surrounded by it, and growing up in London, I had access to some of the best music, theater, and art in the world. Until recently, I didn't realize how much influence having free access to all the museums in London had over my life. Even now, if I'm there and it's raining or have a spare half hour, I can wander into the Tate or the National Gallery. It's an extraordinary gift.

Close, Closer identity for Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2013, designed by Zak Group

What did you learn about yourself when you were studying?

I studied architecture at the University of Bath in England, and the first thing I learned was that I wasn't good at architecture [laugh]. I discovered that I had no design skills whatsoever. Still, I loved reading and writing about architecture, a skill set that not everybody had, and I found out early on that I was naturally good at organizing things. So consequently, I volunteered to lead the Architecture Society. We organized talks, visits, and trips, and we had parties. And so, I discovered other skillsets I had of being this sort of convener of people.

I started to understand how important it was for architects to have an opportunity to learn about other types of architecture outside of books and lectures. So, I brought what I learned through my reading or research and then organized talks for the group, which I do now, [laugh], but on a larger scale. It's zero surprise to anybody I studied with that I ended up doing this. My first experience as a critic was an internship at a magazine called Building Design, a weekly newspaper in the UK. While there, I joined the editorial team, and my first published piece was in the summer of 2001. So now, I am well into 20 years [laugh] of doing this [laugh]. That age was an exciting milestone to be published, to interview architects, and to learn about the processes behind their work. I stayed writing and working with that editorial team throughout my time at university, and I'm still in touch with most of them now.

How has your work evolved?

I studied architectural history at the Bartlett UCL and was a paid journalist and writer at various magazines like RIBA Journal, Frame, and Wallpaper. Eventually, I joined Icon and became the architecture editor. Then, chance stepped in, and I was recommended by a friend to apply for a job as a curator of architecture in China. I got the job and became the European curator of the Shenzhen Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture. This was 2009, and it was a significant life change -- I moved to Beijing and lived there for a year.

How was the language barrier? Were you able to learn the language?

I took Chinese lessons and tried to integrate myself into the community of international curators, writers, and my Chinese colleagues, which was great. I lived in a beautiful courtyard house in a Hutong in the old part of the city, and my friend and I had parties and barbecues all summer. It was super special. During that time, I began writing for international titles from China, and I gradually started to be approached by others, which had a snowball effect on my career. This time was exciting because of the international travel. One week you're in China. Next month you're in Korea. Next year you're in Italy. I was all over the place, and after five years of international exhibiting and writing, I was asked to apply for the job of architecture curator at the Met, and that's when I decided to stop traveling and stay in one place.

“To me, success is about adding many more voices and platforms for those voices to ensure that curation and writing are viable careers for anyone interested in contributing to the conversation.”

While at the Met, I read that you were a one-woman show, and you had to carve out what that job looked like. Can you elaborate?

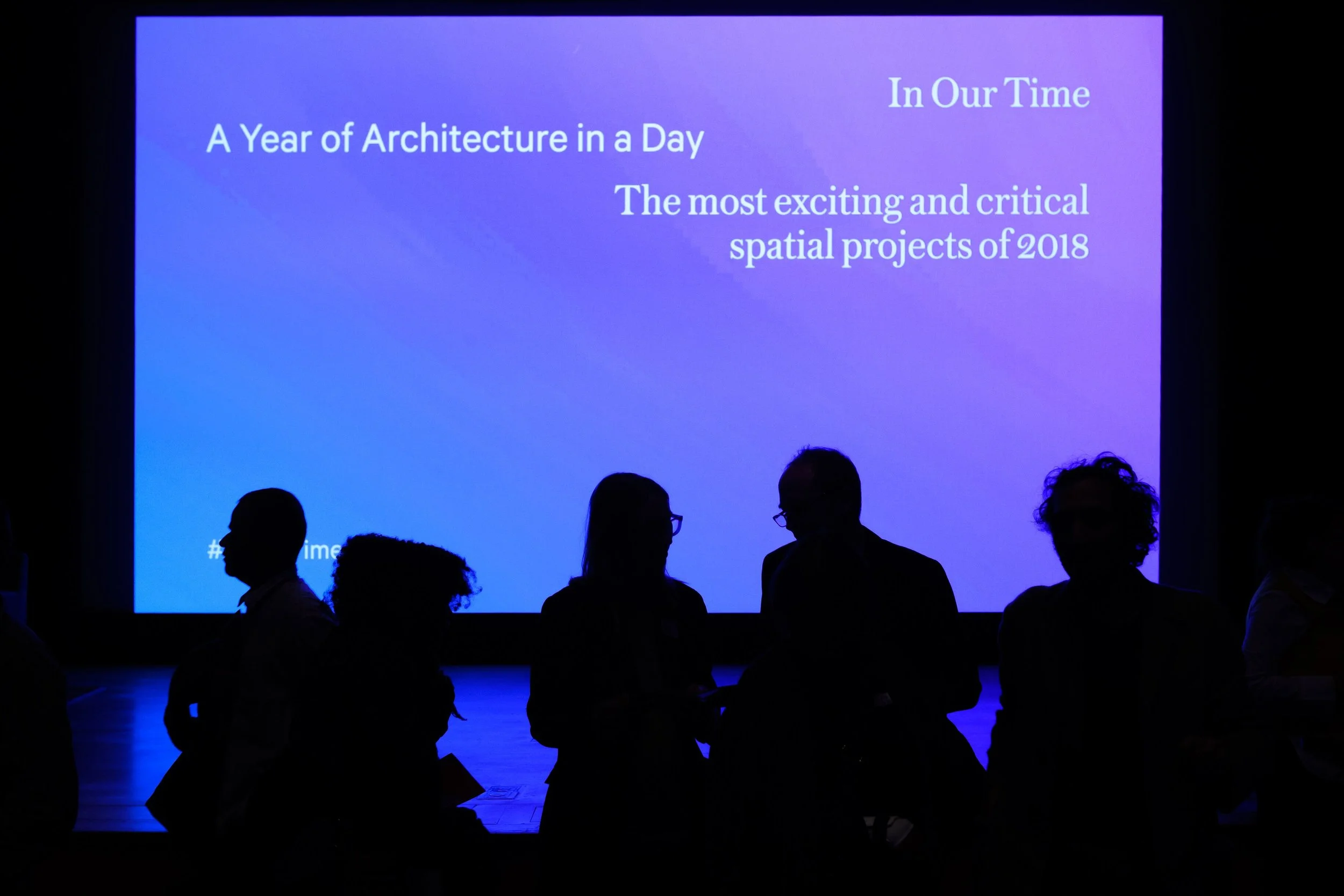

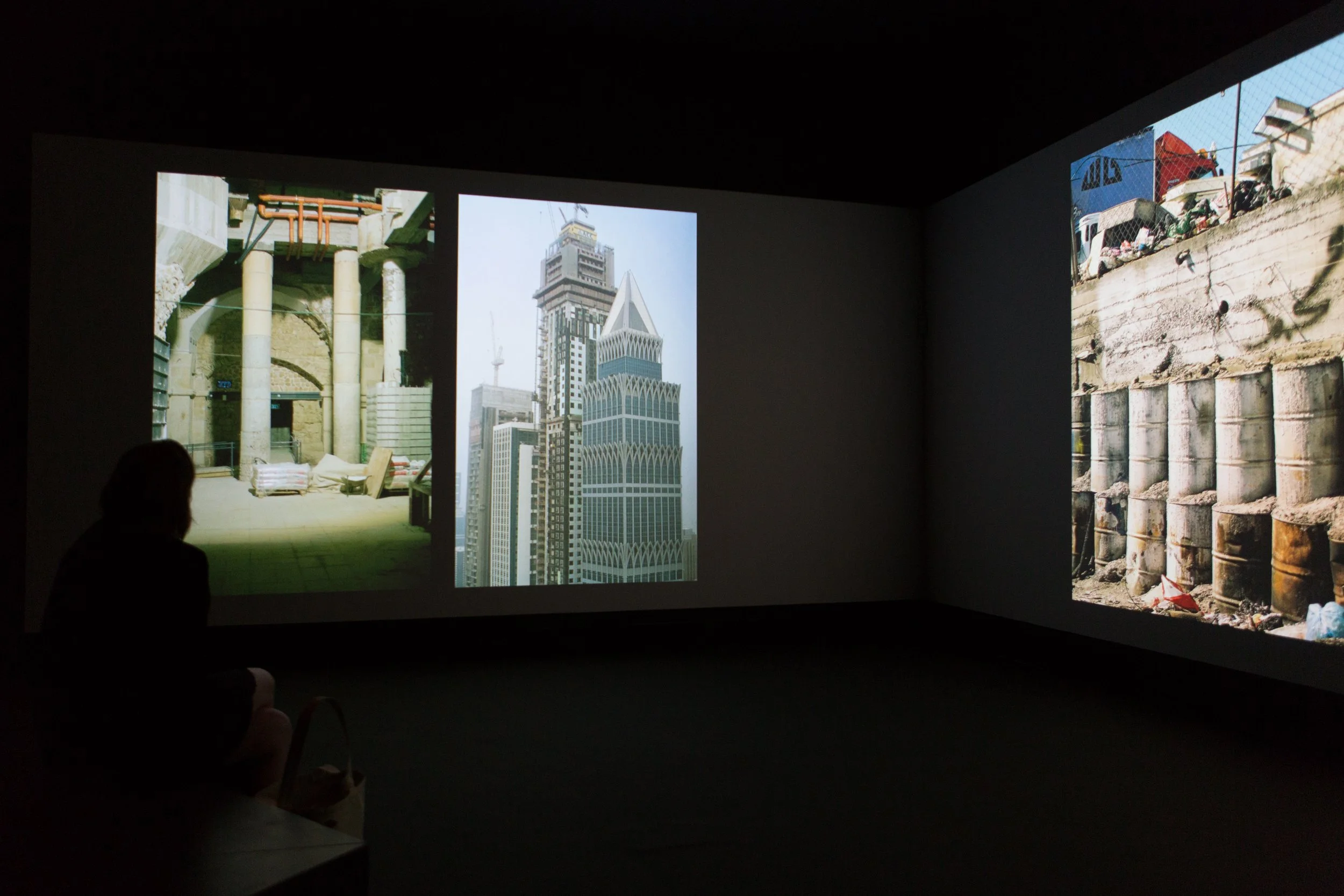

I was the first architectural curator in the department of modern and contemporary art, though there had been many other types of architectural expertise at The Met since its foundation. I created a lot of alliances with different departments and worked closely with the graphics, communications, and education departments. I felt like a roving curator because everything in my field touched every other field. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is embedded in architecture and has so many literal components of the built environment designed within it. There are period rooms throughout the museum, staircases, facades, Venetian courtyards, of course, the actual Temple of Dendur. There is an incredible drawings and prints department, and a photography department with historical works from the beginning of architectural photography. Although it was a one-woman show in the sense that I didn't have my own department, team, or anything, I felt liberated to collaborate and work with many of my colleagues across the museum, organizing events, publications, exhibitions, and installations that were probably outside of the strict definition or job description Working with colleagues, I organized an annual conference called "A Year of Architecture in a Day." The last iteration of it had people queuing up around the museum!

That's incredible, especially for a natural connector.

It was very cool.

I love that architecture can ignite a curious mind. When I think of architectural photography of ruins, I consider how an artist might interpret it as folly. I'm sure that ignites one's imagination — there are so many different avenues you could go down.

I was lucky to work with many artists while I was there and worked closely with the collection. The practice of architects like Francis Kéré was of genuine interest to researchers working with sub-Saharan African historic architecture from the Sahel region in North Africa, and vice versa. There were many ways for contemporary architecture and art to inform historical perspectives. Yeah, it was amazing.

The Theater of Disappearance, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Courtesy of Hyla Skoptiz.

PsychoBarn, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Where are you at in your career today? What is on your mind most of the moment?

I left the Met and based on the success of the annual conference, I found support through philanthropists and collaborators to begin The World Around, a nonprofit platform for contemporary architecture that is in quite a significant transition. Our first conference - our 'Annual Summit' was held in late January 2020, so we had just started, and the pandemic hit. It has been a rollercoaster to run a nonprofit organization these last years, but through creative partnerships and collaborations with other institutions, we are now stabilizing.

I credit our survival to the extremely talented, kind, and brilliant community involved with and supporting The World Around. This network includes everyone from our board of advisors and trustees, who keep me sane and help me feel supported, to the TWA team, staff, interns, and friends in other organizations who want us to succeed.

The World Around is about to have its fourth annual summit at the Guggenheim Museum on April 22, which is top of mind. To be honest, the top of my mind is a bit of a scramble as I'm working on curating, fundraising for the event, and coordinating our first-ever prize for people under 25, called the "Young Climate Prize." For the past three months, we have organized mentor sessions and weekly lectures for a cohort of 25 under 25s. Soon they will submit a new application, and an international jury will choose three winners who will travel to New York and present their work at the summit.

Looking back, what has been the biggest challenge, and how do you manage through disappointment or perceived setbacks?

I am someone that thrives under pressure and responds to setbacks well. Most of the things I have achieved have resulted from negotiation, a lot of nos, [laugh], and quite a lot of persuasion, you know? Many of my most successful projects have been the result of setbacks. The other challenge has been Covid, especially regarding The World Around. But, out of that situation, we created connections with other institutions and made a lot of long-term partnerships that otherwise could never have happened.

What did Covid do to curation? Did it impact the way things are curated and stories are told?

The Black Lives Matter movement had more impact on curation because it created more visibility for the stories people wanted to tell and hear about instead of the same old, mostly white, mostly male faces and names. I have always tried to foreground a more pluralistic approach to architecture and a broader interpretation of who and what should be included in the conversation about architecture. As a result, we were able to reach an audience interested in what architecture is about outside the mainstream line of thought.

“We ask ourselves how we guarantee that whatever we are supporting, whatever we’re championing, is worth the material, the extractive cost of that material, and is solving necessary problems that it is effective and efficient and contributes something of value. That is how we need to start thinking about architecture, but also about our own lives.”

What are you most excited about right now?

I'm most excited about The World Around and our Young Climate Prize, a mentorship program for people under 25 who have their own climate change-focused projects. We started it as a pilot project because having a profound conversation with the next generation about climate change was essential. I wanted to do something valuable and productive with our platform and the intelligence and brilliance we have at arm's length. I was wondering if we would get any applications, but we received 300 from 58 different world countries. What I found so moving about the projects we received and the people we met is that these are young people on the front line of climate change. For them, droughts, floods, changing shorelines, migration, misinformation, pollution, corruption ... none of this is abstract. Our cohort is exceptionally well-informed, intelligent, and motivated, from researchers to engineers, poets, architects, and scientists. I know they will generate profound and meaningful change in their lives. Amongst the cohort of 25, they are already finding connections between themselves and are collaborating in a way that lifts my soul.

I live in New Orleans and know Louisiana's shoreline is receding yearly; small towns on the Gulf coast are gone — entirely underwater. I see more change come from curators, writers, and photographers than senators and governors. The action that I'm seeing has its genesis in art. I can't wait to learn more about this competition and the winners.

Well, on April 21, three of the twenty-five will be selected by a jury to come to New York and present their work at the Guggenheim, so I can't wait to share their work with you and with everyone.

Who are you learning from right now?

I'm learning from that group of young people. When I hear those young people talk about ways to mitigate climate change, create interventions that help with adaptation, or how they plan to generate access to knowledge and infrastructure is inspiring. I admire most, if not all, the applications we received for Young Climate Prize. They were excellent.

In Our Time: A Year of Architecture in a Day, Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Book for Architects, courtesy Wolfgang Tillmans and David Zwirner Gallery

The World Around, designed by 2x4

What impact would you like to have on the world?

I have always been driven by sharing what I know and love about architecture with as many people as possible. I hope that The World Around will continue to give a platform to new talent and be part of sharing progressive, inspiring, playful, and brilliant ideas and people with our huge global community.

Kate Wagner is a critic who started a blog called McMansion Hell, and what I love about her writing is the levity. Architecture can be so severe. So, whenever I hear someone make things playful, it makes the discipline more approachable. I'm grateful that's part of your mission.

Yes, being playful is a way to bring people in and take architecture off its self-appointed pedestal. Much of the academic conversation and writing and communication around architecture is heavier going; that's only one component of what the discipline needs to make progress. To me, success is about adding many more voices and platforms for those voices to ensure that curation and writing are viable careers for anyone interested in contributing to the conversation.

We have had filmmakers, VR games, music videos, and many others at The World Around, which should add an exciting dimension to the architecture community. Bringing these other elements into the conversation makes the discipline more accessible.

What advice do you have for those starting their careers? And would your direction be any different for women?

I started my career from scratch and didn't know what I was doing. I genuinely just started to do things related to my interests. Whenever I'm asked for advice, I recommend people try to get something—anything—done. If you're someone that wants to be a curator, you are going to need to make an exhibition. Many curators start by curating something in their homes, kitchens, university galleries, office spaces, local libraries, or pubs. You can curate objects, make things, write things; you can negotiate, barter, beg, or borrow space to put on a show.

Yes, eventually, you need people to help fund your efforts, but there's always a way to creatively succeed by getting something is done that doesn't require a financial investment. My career proves that it doesn't need wealthy parents. It doesn't require friends and family in the industry.

It is possible to generate beautiful, meaningful spaces through your own drive, your own inner engine.

From a curator's standpoint, how do you feel about the recent climate protests targeting works of art?

I believe those protests are effective because they are getting to the heart of the problem, which is that most people would be more horrified about paint being thrown on a painting and the value of that painting than they are about the demise of the entire planet. Millions of people will be displaced, and hundreds of millions of people will be affected in one way or another by climate change. You can't quantify that.

The protestors did not change the paintings' value and were discerning about which pieces they targeted. These people are not against art; they are making a statement to the art market as a signifier of inequalities. Watching the media sensationalize the harm done to the paintings and not acknowledge the damage done repeatedly to the environment is disheartening. Instead, we should be highlighting the events that are taking place daily. They're brilliant, and most people will agree they created something memorable and impactful.

I couldn't agree more. How do we protest inefficient or unsustainable architecture? What does that look like? It opens all sorts of disciplines to criticism and conversation. I appreciate you sharing your thoughts.

It's an important issue. As The World Around becomes more involved in climate change and the conversations around architecture, the apparent contradiction is that there is no sustainable new building. There is no good way of building green architecture — there will always be a carbon footprint as long as you build. So, the question for us is, what will we show [laugh] at The World Around?

We ask ourselves how we guarantee that whatever we are supporting, whatever we're championing, is worth the material, the extractive cost of that material, and is solving necessary problems that it is effective and efficient and contributes something of value. That is how we need to start thinking about architecture, but also about our own lives.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.