Access and Ubiquity: Besler & Sons' Erin Besler on the Social Aspects of Construction, Proliferating Points of Entry, and Saying No

By Julia Gamolina

Erin Besler is faculty at Princeton School of Architecture and co-founder of Besler & Sons, a studio that designs buildings, software, objects, exhibitions, and interiors. Their work has been exhibited at venues internationally, including the MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Chicago Architecture Biennial, and Shenzhen and Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Architecture/Urbanism as part of the group exhibition Now, There, where they received the UABB Bronze Award. Recently, they were awarded a Graham Foundation Grant for their debut publication, “Best Practices: A companion to architecture and its messy relationship with building materials, signage systems, communication equipment, plant life, and people.”

Erin received a Bachelor of Arts from Yale University and a Master of Architecture with Distinction from the Southern California Institute of Architecture, where they were awarded the AIA Henry Adams Medal. They were 2019 United States Artists Fellows in Architecture & Design, a recipient of the Architectural League of New York Young Architects Prize and a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome. Erin was previously an Assistant Adjunct Professor at UCLA in the Department of Architecture and Urban Design, and awarded the 2013-2014 AUD Teaching Fellowship.

Erin has a particular interest in the social and political aspects of construction, social media, and other platforms for producing and sharing content where interactions rely less on expertise and more on ubiquity. In their interview with Julia Gamolina, Erin talks about their goals for access, the financial situations too many architects face, and taking care of oneself and others, advising those just starting their careers to learn when to say yes and when to say no.

JG: Tell me about your foundational years — where did you grow up and what did you like to do as a kid, and how do you see those experiences reflected in your life and work now?

EB: I grew up in Chicago. I’m an only child and maybe because of that I was always trying to belong to something that felt bigger, like a large family. I played a lot of team sports growing up, and I loved being part of something collective, something shared, and also something social. I think that has a lot to do with the way we run our office, the way we work with our team, and the perspective we bring to projects, always trying to multiply the sites of design, producing opportunities for public participation and engagement, sharing expertise rather than amassing it, and doing that more through ubiquity than exception.

Roof Deck at MoMA PS1, 2015. Courtesy of Besler & Sons.

Shed in Illinois, 2020. Courtesy of Besler & Sons.

How did you choose Yale and SCI-Arc to be the places where you studied architecture?

I’ll begin by saying that one of the sports I played growing up was ice hockey. I was interested in hockey from the time I was about three, and my mother signed me up for figure skating, so hockey practice was just after my lessons. For a long time I was told, “Girls don’t play hockey.” But when I was in kindergarten, I had a classmate with an older sister who played. My mother gave in. I joined a boy’s team but the coach wouldn't let me play much. At some point I realized that the goalie was on the ice the entire game and so I switched to goalie and I got pretty good! I went to the Olympic Training Camps in Lake Placid and Colorado Springs. The Yale Ice Hockey Coach was a coach there. I had also been taking some architecture courses at my high school, because I wasn’t happy with the house I lived in, and wanted some mechanism and path to change it. My parents still live in that house and now I realize it’s actually a pretty cute somewhat utilitarian ranch house. Anyway, Yale was one of the few schools that had ice hockey and architecture.

After undergrad I moved back to Chicago to work, but with a BA I’d eventually have to return to school to get an M.Arch if I wanted a license. Well…one year turned quickly into five years! I was pretty deep in practice but at the same time I felt like I had no idea what I was doing. Somewhere in there Ian and I met and got married. SCI-Arc seemed like an interesting place — it didn’t have a campus, it didn’t look like a school but was very much one, and it was in a city that felt like Ian and I could both have lives outside of any institutional affiliation.

“I loved being part of something collective, something shared, and also something social. I think that has a lot to do with...the perspective we bring to projects, always trying to multiply the sites of design, producing opportunities for public participation and engagement, sharing expertise rather than amassing it, and doing that more through ubiquity than exception.”

How did you get to starting Besler & Sons? What are you focused on these days?

In 2015, we needed to form an office — or actually, needed to be prepared to carry large amounts of liability insurance for the MoMA PS1 project, so we needed an LLC, and a business name. Up until that point Ian and I collaborated but worked somewhat separately in a model where we passed projects back and forth. Ian’s background is in Media Design and so our approach to projects and areas of interest are somewhat different. The name Besler & Sons, was a sort of endearing jest that Ian’s MFA program director started. But we liked it because it seemed to characterize a family operation which we very much felt like we were, and still are.

I love it. What about Besler & Daughters though, ha!

Haha! We actually do have the web domain www.besleranddaughter.com, in addition to beslerandsons.com. We often move back and forth between them as a way to test new online platforms, interactions, and ways of structuring our website. We’re focused on everyday forms of building, the social aspects of construction and the constellation of people, places, and practices that are tied together by the building site. The building site and construction more broadly are often kept separate from architecture. This idea has arguably been productive for the field, but that separation is also false. It’s all entangled and architecture has been doing a great disservice by not acknowledging this.

So we’re focused on the building site as host to some of architecture’s many remote participatory practices. It’s important, I think, for architecture to recognize that some people involved in the life of a building choose to participate while many more do not. And there’s a power dynamic there that’s negatively affected a large percentage of the world.

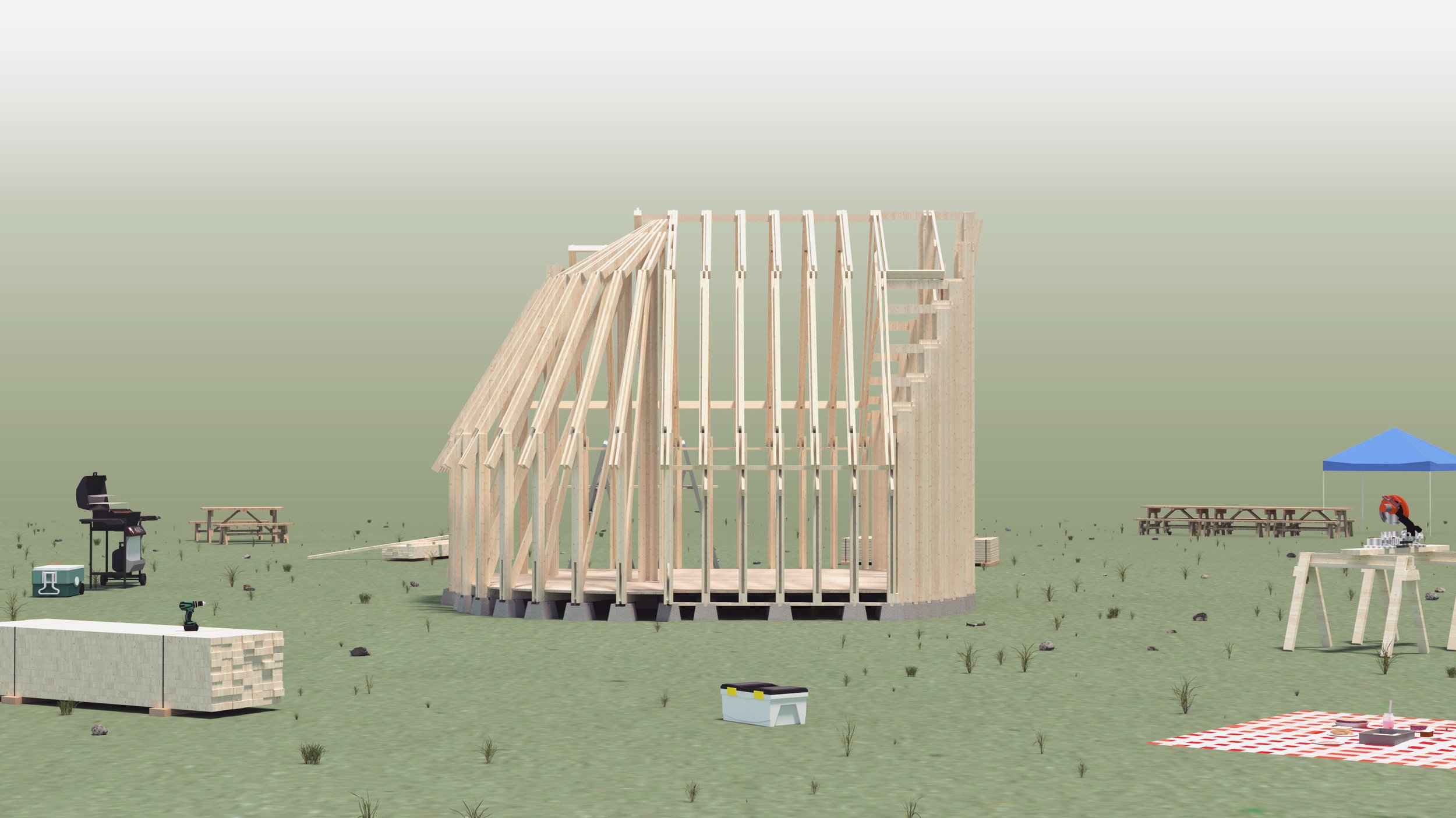

Barn Frame, NJ, 2023. Courtesy of Besler & Sons.

Barn Raising in NJ, 2023. Courtesy of Besler & Sons.

Barn Raising in NJ, 2023. Courtesy of Besler & Sons.

Looking back at it all, what have been the biggest challenges? How did you both manage through perceived disappointments or setbacks?

Some of the biggest challenges have been and continue to be pretty mundane: financial, maybe compounded by grad school loans and job precarity. More recently, I’ve been juggling that with now having a toddler. I delayed having kids for a long time because of these challenges, always feeling unstable or one paycheck away from not being able to afford basic living costs. For a long time this wasn’t something I felt like I could talk about, or had to hide. We self-funded a lot of projects and incurred massive amounts of debt, but at the same time, because we were just getting started, we felt like we couldn’t say “no” to any project, and a lot of them offered very little or no compensation.

This is all far too common. Thank you for sharing this.

I’m not sure we’ve overcome it, but I think we’re more aware of it, and also more comfortable talking about it to try to break the cycle and not pass these things down to the next generation of architects. A lot of people are talking about these issues in different ways as they relate to labor, unions, compensation, time, capitalism, so I don’t feel as alone in this situation, and in that sense it’s been just a little easier to say, “Thank you, but no,” to some projects. Learning how to say no has been important, but also hard. It’s not because we don’t want to do the project or work with the client — quite the opposite actually — but because we just aren’t in a position where we can take on work for free. And a value system that does not seem to value us is a hard thing to reconcile.

What have you also learned in the last six months?

I’ve learned I have to take better care of myself. That sounds small or like something one might have already learned in life, but it’s a really hard thing to do. This is a field that has a tendency to engrain the opposite and on some level that starts in architecture school. It’s a hard thing to unlearn.

“We’re constantly asked to over-extend ourselves and those asks come from many different directions. Oftentimes we sacrifice our own well-being. Take care of yourself and extend that sense of care to others.”

For sure. I remember getting the side eye from some of my professors in architecture school when I left studio at 4:20pm on the dot when class was over, to go run with the running club. I eventually stopped running with the club — but happily running a lot now. On that note, what are you most excited about right now?

I’m working on designing and choreographing a community barn raising and researching the barn as a site where commonly held distinctions break down like between experts and amateurs, between individuals and collectives. Trying to get it off the ground so to speak is an ongoing endeavor! This is also something I'm working on with students in a class I’m teaching which looks at barns from community raising weekends and feminist pedagogical projects, to back-to-the land conversions and acts of preservation.

In this vein, who are you admiring now and why?

We were in the same PS1 competition with Andres Jacque/Office for Political Innovation’s in 2015. We lost and they won. Anyway, there’s a lot to look at there but maybe more than the visual, I appreciate how research and design are entangled in a kind of activist architectural project and one that’s collaborative. There’s intentional politics in the entanglement that equally considers bodies, environment, material, maybe as a form of resistance or counter to dominant architectural narratives. I think that’s where we need to be today.

Somewhat adjacent to architecture I also really appreciate the work CLUI is doing, the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Los Angeles. How they produce public programming that considers both very large scale human impacts on the land, and things that are less part of the visual field but equally significant. They offer ways of looking and listening at the intersection of art, environment, architecture, infrastructure, anthropology.

I like the plurality of both of these practices.

Ranch House, 2020. Courtesy of Besler & Sons.

Entire Situation, 2015. Courtesy of Besler & Sons.

What is the impact you’d like to have on the world? What is your core mission? And, what does success in that look like to you?

Architecture continues to be a very difficult field to access, both in terms of hiring an architect, and also becoming one. We’re committed to a practice that’s less concerned with exclusivity — we work counter to it, and are more invested in access and ubiquity. For a long time we’ve been interested in expanding the definition of architecture through participation with amateur creators, construction trades, and design software. I still think that’s true on some level, but I also find that the definition seems less important than proliferating the points of entry.

Finally, what advice do you have for those starting their career? Would your advice be any different for women?

You don’t have to say “yes” to everything. It’s ok to say “no.” Learn how to say it and sit with it. It’s hard, and may not be comfortable. We’re constantly asked to over-extend ourselves and those asks come from many different directions. Oftentimes we sacrifice our own well-being. Take care of yourself and extend that sense of care to others.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.