Breaking the Cycle: Despina Stratigakos on Historical Amnesia, the Magic of Architecture, and Creating Conditions for Change

By Julia Gamolina

Despina Stratigakos is an internationally recognized scholar of diversity and equity in architecture. Her books, including A Women’s Berlin: Building the Modern City (2008), Hitler at Home (2015), and Where Are the Women Architects? (2016), explore the intersections of power and architecture. She has published extensively on barriers to equity and diversity in the building professions, including stereotypical representations of architects in history books, the lack of diversity among elite architecture prize winners, and the absence of female architects and architects of color in Hollywood films.

At the University at Buffalo, Professor has served as Vice Provost for Inclusive Excellence since 2018, focusing on UB’s efforts to create a culture of inclusive excellence and enhance diversity, equity and inclusion across the campus community. She also serves as chair of the Inclusive Excellence Leadership and Advisory Council. An engaged scholar, Professor Stratigakos participated on Buffalo’s municipal Diversity in Architecture taskforce and was a founding member of the Architecture and Design Academy, an initiative of the Buffalo Public Schools to encourage students from diverse socio-economic backgrounds to pursue degrees in architecture. Professor Stratigakos received her Ph.D. from Bryn Mawr College and taught at Harvard University and the University of Michigan before joining UB’s Department of Architecture in 2007. In her conversation with Julia Gamolina, Despina talks about why she does what she does, advising young architects to persist.

JG: How did your interest in architecture first develop?

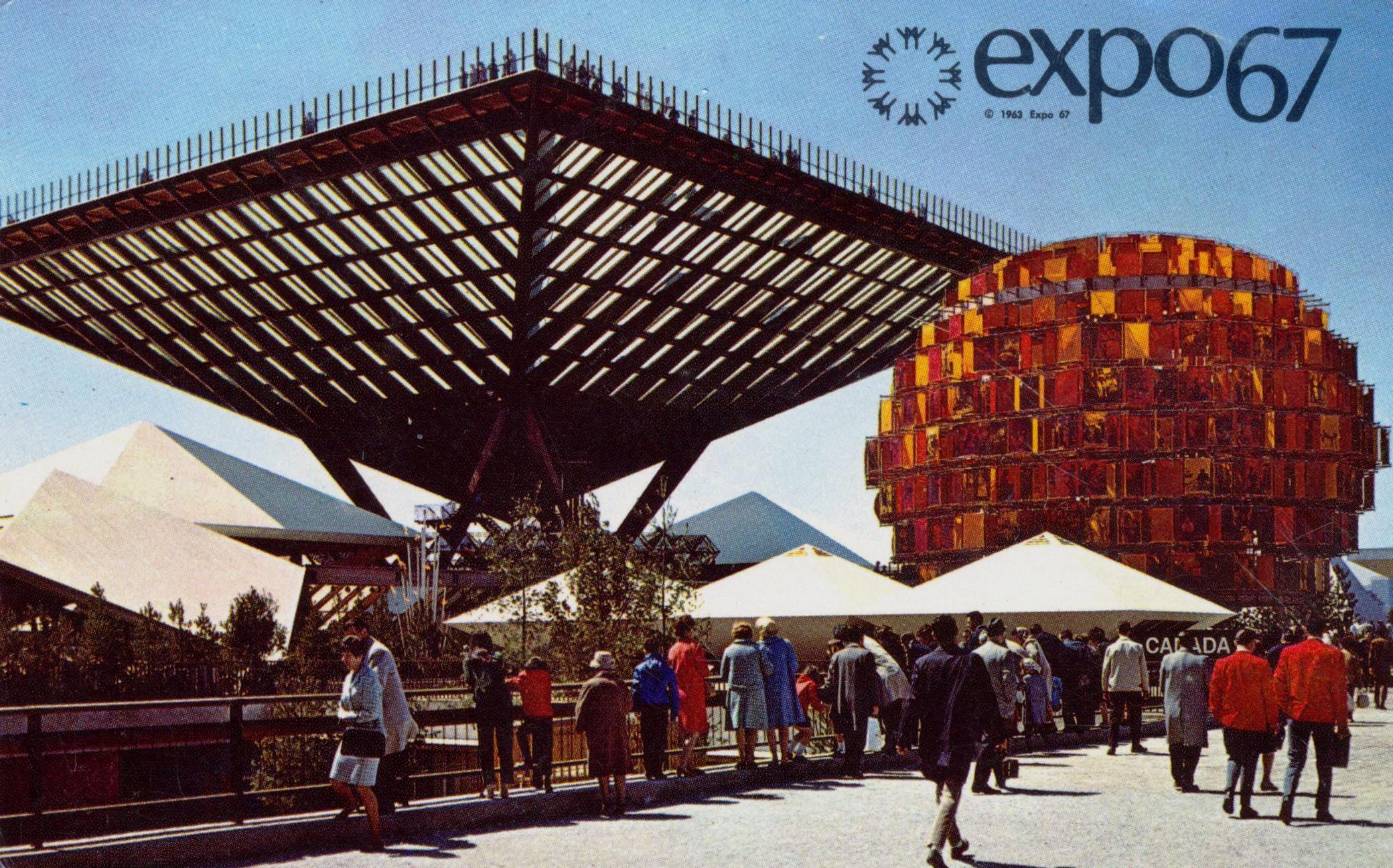

DS: There was a pivotal event early in my life. The World’s Fair opened in Montreal in the summer of 1967, and I was young enough to wander off and be taken to the pavilion of Lost Children [laughs]. The exhibition was a wonderland of buildings, bright and colorful, in fantastical shapes, and I was mesmerized by this magical world.

I remember riding through Buckminster Fuller’s dome on the Minirail and visiting Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, a building made of blocks. For many children, the world is a magical place, but in this case, it truly was a fairy land of architecture. I don’t think I’ve ever lost that feeling of wonder that comes from experiencing extraordinary spaces.

Postcard for the 1967 World Expo.

What did you first study?

I studied anthropology as an undergraduate. I was drawn to understanding cultural differences and how to navigate them, having grown up in Montreal as a child of Greek immigrants, and in a period when Quebec was experiencing political terrorism, including bombings and kidnappings. During the October Crisis of 1970, then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau evoked the War Measures Act, suspending civil liberties. It was a terrifying example of what can happen when cultural and political divisions become so deep, you no longer trust your neighbor.

But even in peaceful times, I was closely attuned, as are many children of immigrants, to cultural cues, and to reading them so that I could navigate the world around me not just for myself, but also for my parents. Children of immigrants often serve in this kind of translator role, whether literally or figuratively, for family members. That experience led to my interest in how we can communicate across difference and how we can build societies and communities that absorb difference and grow stronger, rather than fracture, because of it.

You then went on to UC Berkeley and Bryn Mawr College to study art and architectural history.

Yes, but I never lost my interest in anthropology. Throughout my graduate studies, I continued to look at space and architecture through a social and cultural lens. More and more, I became interested not only in cultural meanings, but also in how they relate to power, and how power is embedded in all types of different milieus.

When I began to teach in architecture schools, I became fascinated by the culture of the schools themselves, which was quite different from what I had experienced in the humanities. That led to exploring their pedagogical practices and who they empower. From there, I began to wonder about the transition to practice and differences in the career paths of men and women.

What were your takeaways from your PhD?

My dissertation examined what happened when women first began to enter architecture at the turn of the twentieth century. As a young professor teaching in architecture schools, I was surprised to realize how many of the hurdles that had existed a hundred years earlier for female students were still around. That made me realize that history can be a powerful tool to unpack our values and examine our practices today in order to denaturalize them so that we can obtain some critical distance.

These norms have been embedded in architectural education and office culture for such a long time that they come to seem natural—just the way things are and have always been. By going back to the moment when they were first articulated and encoded into educational and professional practices, you can see that they are constructed and can therefore be dismantled. For example, where did the idea come from that you have to choose between being a successful architect and a good parent? I discovered that this idea arose a century ago as a way to discourage women from entering architecture, when they were told that you could either be productive or reproductive, but not both. Unfortunately, that assumption is now so deeply engrained, both men and women suffer the consequences.

For me, history is a tool of intervention, a critical wedge that allows you to unpack what seems natural and eternal. I hope that my writing, which ties together past and present, sheds light on how we are sometimes caught in old patterns, but also empowers others to say, “It doesn’t have to be this way.”

Tell me about your 2016 book, “Where Are the Women Architects?”

The title comes from a question that kept reemerging in newspaper and magazine articles that I read going back over a hundred years. Time and again, reporters noticed the absence of women in architecture and wondered why that might be. It was a question that I found myself asking, too, as a student, when I first began to look for women architects in history books, museum exhibitions, and at prestigious venues. The architecture world was so visibly, overwhelmingly male.

While researching the book, I found an article from the 1870s that pondered the absence of women in architecture, and I thought: Here we are, 140 years later, still asking the same question! So the question became the driver for the book and a way to emphasize that gender equity isn’t a new discussion. Realizing how long people had been talking about women’s exclusion from the profession was truly alarming to me. It revealed a cycle of acknowledging and then forgetting the profession’s gender problems. I wrote the book to try to expose and disrupt that cycle.

Why did the issue keep getting forgotten?

It seems like a case of historical or professional amnesia. The question of women’s under-representation in architecture would be raised, followed by discussions about the challenges they faced and how to address them, and then the whole thing would be forgotten again. Then the cycle would be repeated, again and again, through the decades. I didn’t know why the cycle kept repeating, but the pattern—of noticing and forgetting—was clear. The book was intended as a provocation, a means to expose the cycle and to help find a way out of this Groundhog Day in architecture.

How do we avoid continuing this cycle?

By knowing our history, finding allies to broaden the struggle, and using the power of new tools to raise and maintain awareness. When you look at the discussions happening today—the events taking place globally, the articles around the #MeToo movement, but also the recognition of women’s work, including the website you have created—the movement for gender equity in architecture is more powerful and more visible than ever before. I believe we will succeed this time in breaking out of the cycle and move towards lasting change.

I’m so glad you think this is it, and will end here.

For the first time, we have the activism of a younger generation of women architects joining with the voices of women who have pushed for change for a long time, and that combination across generations is very powerful. We also see new alliances across gender, as young men increasingly identify with concerns that have traditionally been labelled “women’s issues.” These young activists, male and female, are deeply concerned with making architecture a more welcoming profession for all, which also means addressing its longstanding issues around race, class, and sexuality.

For example, there is a wonderful Australian website called Parlour dedicated to gender equity in architecture. Their contributors include men who write about what the issues mean for them, such as their desire to find work-life balance or to explore collaborative forms of working that go beyond traditional norms of architectural practice. There is a deep shift happening in architectural culture that will have a broad positive impact, and not just for women.

A woman builder making repairs to the roof of Berlin’s city hall, 1910.

Where are you in your career today?

I’m in an interesting place. A while ago, I found myself thinking about the role of administration and senior leadership. I knew that it would take me away from some of the things that I love, such as teaching in the classroom and the day-to-day contact with students.

But I also realized that it was the right time for me to put my experiences to use in a new way. I was given encouragement in that direction by Robert Shibley, Dean of the University at Buffalo’s School of Architecture and Planning. He exemplifies the power of a good mentor to open new pathways by changing your ideas of where you stand. I was lucky to have that—many women in architecture struggle to find mentors, since mentors tend to fall into the “mini-me” phenomenon of wanting to mentor people like themselves. Over the past few years, I have served as Deputy Director of UB’s Gender Institute, as Chair of the Architecture Department, and, since last year, as UB’s Vice Provost for Inclusive Excellence. Every day brings new challenges and the chance to put theory into practice. Much of my work focuses on building collaborations and partnerships in order to create the conditions for change.

What have been some of your biggest challenges?

One of the toughest challenges I have faced I am happy to say is becoming a thing of the past. When I first started working on gender equity in architecture two decades ago, too often I felt like the lone voice in the room pointing out the need to consciously consider women in our planning and strategies. That can be hard to sustain, and I looked for and found support and allies in many places. In Where Are the Women Architects?, I acknowledge the “village” of women who have struggled alongside and encouraged me in the long fight for gender equity.

Today, I am grateful for the voices of young activists who have emerged in the past few years and the inspiration and energy they bring. I am also deeply grateful for women such as Denise Scott Brown, Susana Torre, and many others, who kept the battle going for decades, at a time when there was little support from their colleagues. We owe them an enormous debt, and we can only pay it forward.

What have been the biggest highlights?

The village! All of the wonderful allies I have made over the years who have sustained me and who, I hope, I have also helped to sustain. These friendships have been forged over a shared vision and common struggles. That community and our experiences of collaboration—we have come together to talk and plan in cities around the world—have been an enormous gift in my life.

I can’t say it enough: it is an absolutely joy to see how a younger generation is pushing the agenda of gender equity forward, with tremendous skill and global reach. When I see young women in architecture who are just not going to take it, thank you very much!—I want to cheer out loud. I have been enamored with architecture since Expo 67, and want as wide an audience as possible to share in its magic. I believe that the hurdles that women have faced are indicative of other issues in architecture that have also made it elitist, so I am very glad for this shift toward a more open, accessible, and democratic profession.

What has been your general approach to your career?

To stay interested and take risks.

It hasn’t always been easy, but I have found ways to do the work I love and that keeps me engaged with the world around me. Sometimes that means trying different things. When my friend Kelly Hayes McAlonie and I collaborated with Mattel on Architect Barbie, we had no idea how it would turn out. We joked that it was going to kill our careers. But it turned out to be a great joy, a project that connected us to girls and women around the world.

Architect Barbie on display at the AIA convention in New Orleans, May 2011.

What advice do you have for those just starting their careers in the field? For women in the field?

One word: Persist.

Although other variables play a role in success, not giving up is often the deciding factor in the long run. As I tell my students who are graduating, when I look back at my own friends who have managed to get where they wanted to be, the common denominator was not abandoning their path when the going got tough.

Finding the power to persist means not going it alone. Find your allies to help guide you and keep you going through the rough patches. It helps tremendously if you have someone you trust who can help you to see your own strengths. Too often, we tend to underestimate our abilities or if we are ready for change.

It is also important to take the long view. Your career will change over time, so stay open to new directions. Consider what those alternate pathways might be for you and how you might prepare for them. When the time is right, don’t hesitate to embark.

Beverly Willis once told me that women can have very long and productive careers, and she is a living example of that—she started her foundation (Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation) to promote women in architecture when she was in her seventies, after many decades of architectural practice. There is so much emphasis on youth in our culture, but it’s important to keep in mind that long trajectory. You may not be able to do everything you want to do now, but you can come back to it later on—it won’t necessarily be lost to you. Have faith in yourself and persist.

Pooja Bhatt, a University at Buffalo architecture graduate student, helping to construct the GRoW Home, the school’s entry in the 2015 U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon. Photograph by Zhi Ting.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.