Building The Impossible: The Real Estate Legacy of Two Black Female Entrepreneurs At The Turn of the 20th Century

National Convention of Walker Beauticians at Villa Lewaro, c. 1924. Courtesy of Madam Walker Family Archives.

By Kate Reggev

You may have heard about early 20th century beauty maven Madam C.J. Walker (her 2020 Netflix mini-series, Self Made, helps). And you may have even heard about her former employer and haircare rival Annie Turnbo Malone. Both were two of the wealthiest female entrepreneurs — Black or white — of the first decades of the 20th century. But you probably haven’t given much time to their architectural and real estate legacies. They each had significant real estate holdings, whether it was their personal homes or the training campuses they commissioned, and used the built environment to convey certain ideas and ideals about themselves and their businesses. At times, they also hired prominent (male) Black architects for the designs. Their empires may have been made in haircare, but they were stabilized and formalized by brick and mortar (sometimes quite literally, from the brick buildings their architects created!).

Annie Turnbo Malone. Courtesy of UMSL Black History Project Photograph Collection (S0336).

The first of the two women to arrive on the haircare scene was Annie Turnbo Malone (1877–1957, née Annie Minerva Turnbo), who was born in Illinois to formerly enslaved Black Americans. Interested in both chemistry and hairstyling from a young age (hilariously, two areas in which I am completely useless), she began developing her own formulas for non-damaging hair straighteners, special oils, and hair-stimulant products for Black women in the late 1880s. She initially made most of her sales door-to-door in Illinois, as Robyn Iset Anuakan details in her dissertation “We real cool”: Beauty, Image, and Style in African-American History.

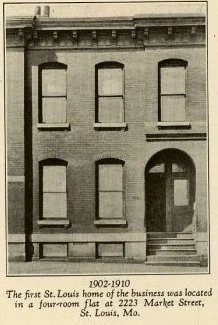

A promotional pamphlet from 1917 for Malone’s products details her story, paralleling the growth of her haircare empire with increasingly impressive real estate holdings: she developed her initial formulas in the rear room on an upper floor of a simple, two-story wood frame house in a small town in Illinois. Then, she moved to St. Louis and upgraded in 1902 to a modest masonry rowhouse with a storefront at 2223 Market Street (at the time, St. Louis was seen as the “Gateway to the Midwest,” providing access to a larger market for Malone’s growing business, especially with the upcoming 1904 World’s Fair).

In 1906, she copyrighted her company to try and distinguish her products from knock-offs and copycats. She called it “Poro” — possibly from the West African language Mende, where it referred to a secret organization that exemplified physicality and spirituality (so, her agents were secret, powerful hair-whisperers, is my interpretation). Outgrowing the Market Street house in 1910, she rented a larger, three-story building at the prominent corner of Pine Street and North Cardinal Avenue in The Ville, St. Louis’ well-known middle-class neighborhood.

The building, originally a single-family home from the late 1870s or early 1880s, had a symmetrical facade, hip roof, raised basement, and masonry steps leading to a columned porch with double doors. The building previously served as the L.C. McLain Orthopedic Sanitarium, according to historic fire insurance maps. I like the idea that the home originally served as a residence, then as a place for healing bodies, and then as a space for educating and cultivating beauty. In a way, it still served as a residence, because the 1910 census indicates that Malone was living there as well.

Poro In Pictures pamphlet, 1917, depicting the story of the company.

Poro In Pictures pamphlet, 1917, depicting the story of the company.

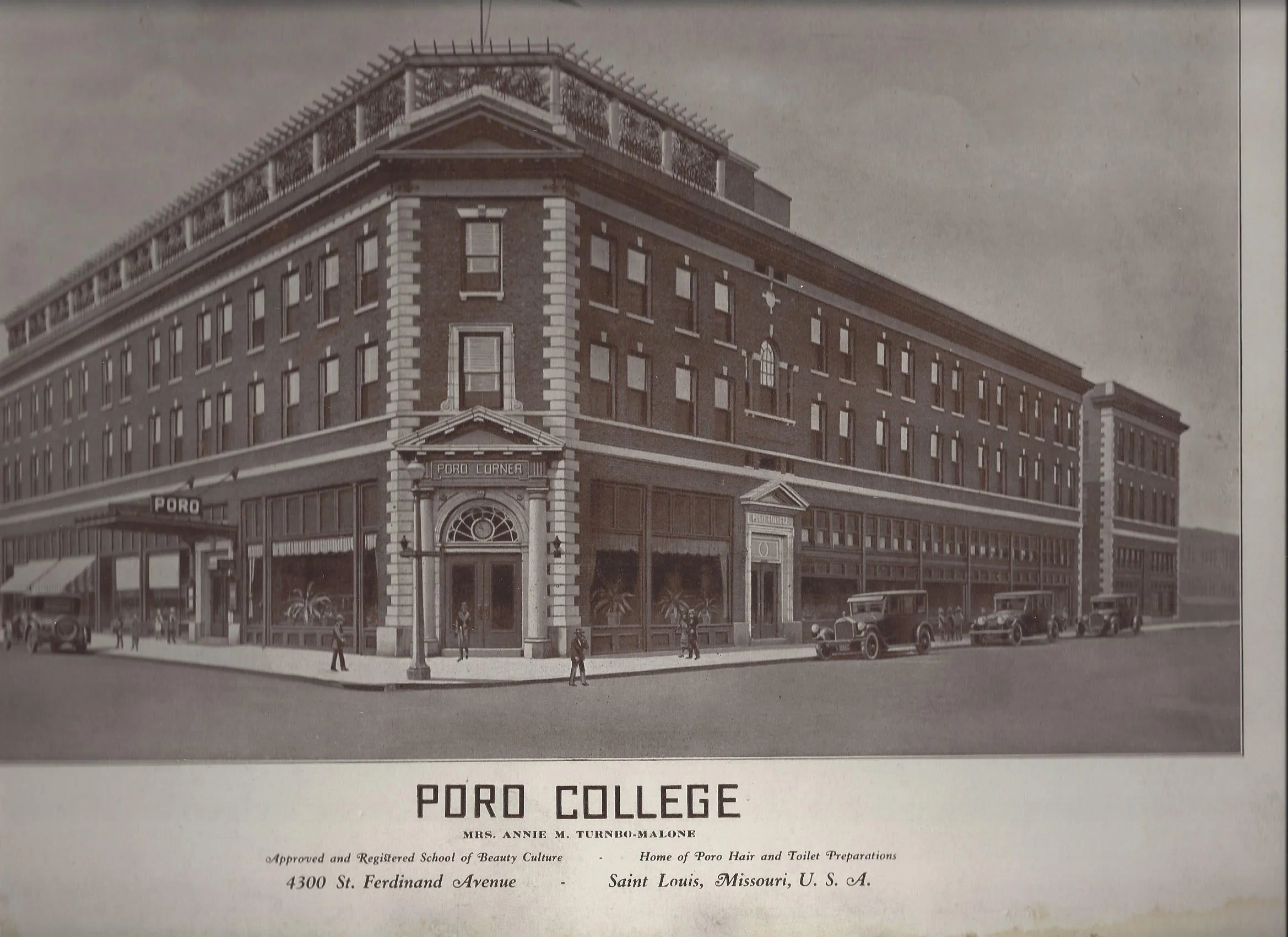

By 1918, Poro had grown so large that Malone hired local architect Albert B. Groves to design a massive three-story, three-acre campus at 4300 St. Ferdinand Avenue that housed anything that the company might need — and then some: a business office, manufacturing operation, training center, a 500 person auditorium… plus a gentlemen’s smoking parlor, cafeteria, dining hall, ice cream parlor (yum), theater, gymnasium, chapel, roof garden, dormitories, and more.

The idea was not just to provide a space to learn about haircare, but also a place to develop financial independence, stability, and, significantly, racial pride. This was especially meaningful because much of the non-Black population at the time viewed Blackness, particularly Black hair, as incompatible with "traditional" white beauty standards (more on that in anthropologist Dr. Evelyn Newman Phillips’s excellent article here). Phillips shows how Malone linked Black beauty to Africa and Christian spirituality, while simultaneously giving them economic opportunities. Women could learn how to sell the products and become Poro sales agents, or they could learn how to use the products and go into hairdressing, perhaps even opening up their own hair salons (there would be dozens of Poro salons across the country by the 1950s).

The Poro College campus was Neo-Classical in style, with red brick and terracotta trim at its pedimented entryways, windows, and watercourses and gave the growing Poro Company even more credibility. Promotional material from the 1920s noted that the building “created an atmosphere which impresses the entrant that Poro College is a sound business institution,” and represented an investment of approximately $750,000 at the time (more than $17M today). We can imagine that as a Black woman in the post-Civil War South, it was important for Malone to have physical spaces that conveyed stability, wealth, and good taste — just like her products.

Its lobby had beamed ceilings, plush armchairs, and an allegorical, three-panel mural along one wall by artist Sylvester P. Annan called "The Apotheosis of the Black Race” (what’s an impressive and aspirational lobby without an equally impressive and aspirational mural?). However, we'd certainly take issue with the theme today: the three panels depicted the so-called “development” of Black people from supposed “primitive” life in Africa, through the “burdens of daily toil” (likely life in the field under slavery or Jim Crow), and then finally the liberated Black race, surrounded by culture, domestic virtues, art, and music — exactly what Malone and the beauty industry were striving to give people, both through their beauty products themselves but also through the job and financial opportunities that Poro offered.

Poro Corner, as the College building was called, quickly became known in the community as more than just a beauty school. Because the city’s Black community was denied access to entertainment and hospitality venues, the campus became a gathering place: “the College would go on to become central to the social and cultural life of the African American community in St. Louis,” explains historian Dr. Katie C.T. Myerscough in her dissertation on St. Louis. Spaces like the large dining room and the rooftop garden were frequently used as a community center and meeting place for religious, social, civic, and other local organizations. According to a 1981 article by historians Donald H. Ewalt, Jr. and Gary R. Kremer, one resident of the Ville even stated that in the 1920s, the social life revolved around Mrs. Malone and Poro.

Poro College illustration, no date. Courtesy of Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Prints and Photographs Collection, N33297.

Given Malone's deep commitment to her local community and the advancement of her peers, the choice of a non-Black architect for such a significant structure in The Ville was puzzling to me. I anticipate that Malone would have liked to have hired a Black architect for such a large commission. She was very involved in investing in her community: she donated tens of thousands of dollars to historically Black colleges and universities, established an orphan's home and a nursery school, and of course her company gave employment to tens of thousands of Black women at a time when most opportunities were closed to them (even white women didn’t act as sales reps for beauty companies at that time!).

But it appears that there simply were not any Black architects licensed or practicing in St. Louis at the time. It wasn’t until the 1950s that Washington University’s architecture school, for example, graduated its first Black students, and although Black architect John A. Lankford (1874-1946) was a contemporary of Malone’s and was originally from Missouri, he moved to Washington, D.C. and practiced there for nearly his whole career.

Instead, it is likely that Malone hired Groves because of his specialization in manufacturing facilities in St. Louis, especially garment manufacturers (for one client, the Brown Shoe, he designed eleven buildings! Talk about repeat clients). It appears that Malone was not a repeat client, though, because a year later in 1919, a $40,000, three-story addition was added to the campus to the designs of local architect William P. McMahon (1876-1954), who then had his office in the Louis Sullivan-designed Wainwright Building. The reason for the change in architect is unclear, given that McMahon's design work encompassed a diverse range of building types including middle-income single-family homes, churches, and commercial structures.

By 1930, Poro College had educated more than 75,000 agents across the United States, the Caribbean, Canada, South America, and beyond. That same year, Malone decided to move the business to Chicago, reported the newspaper The Afro American. She had slowly been acquiring buildings on a specific block in the Bronzeville neighborhood, and felt that moving north to Chicago would open up more business opportunities. (“St. Louis in most of its attitudes is a Southern city,” Malone said, and she felt that the city’s attitudes against her race prevented the business from growing to its full potential.)

Poro College campus, Saint Louis, c. 1927. Digitized by Emory University.

The school’s new site took up half a city block, occupying four three-story buildings for dormitories, a cafeteria, beauty shop, and school. The buildings this time weren’t purpose-built, but they were still grand, to put it mildly: they were turn-of-the-20th century chateau-inspired mansions for the city’s ultra-wealthy, with turrets, crenelations, porte-cocheres, and wrought iron fences and gates (so, a literal gated community for haircare students). Like her other facilities and campuses, Malone lived here too, with the 1940 census noting she lived at the castle-like 4415 South Parkway. Was Chicago her fairy tale, I wonder?

By the 1940s and 1950s, though, Malone and Poro had suffered through a nasty divorce, lawsuits, multiple IRS investigations, and a challenging economy (I’m tired just writing all of that). After her death in 1957, the campus was demolished; today, it is the site of a postwar elementary school. The St. Louis campus was converted into a hotel in the 1930s, and later the Lincoln University School of Law until it, too, was demolished. Even her early salon-home on Market Street is gone, today the site of a low-tier hotel.

Madam C.J. Walker by Addison N. Scurlock.

While Malone’s architectural and real estate legacy has gone the way of the wrecking ball, her rival’s real estate remains and is in fact honored today. Born to former slaves near Delta, Louisiana, Madam C. J. Walker (1867–1919, née Sarah Breedlove) led an impoverished and orphaned childhood, similar to Malone. Married at age 14 and widowed at age 20 (when life gives you lemons…), she moved to St. Louis and found work as a laundress in order to provide for herself and her daughter Lelia (later A’Lelia). In the early 1900s, she began working for Malone and the Poro Company as a sales agent; Walker moved to Denver, Colorado and continued working for Poro while simultaneously developing her own formulas for haircare products.

Within a few short years, Walker’s business saw growth that was nothing short of meteoric: she went from locally selling the products door-to-door to creating a mail-order business managed by A’Lelia, opening her own beauty parlor and school (Lelia College) in Pittsburgh, and establishing a manufacturing base in Indianapolis. In Indianapolis, she bought a house at 640 N. West Street near Ransom Place, a historically Black residential neighborhood (and in fact named after one of her lawyers, Freeman Ransom). The generously-proportioned wood-frame house with a masonry facade would serve as her residence, salon, and office, with a rear outbuilding that Walker added as a production facility — historic fire insurance maps called it a “salve mixing” building.

Madam Walker on the Porch of Her Business, c. 1910s. Courtesy of Indiana Historial Society.

In a 1912 speech at the National Negro Business League (NNBL), she described how she moved up in the world, stating “I have built my own factory on my own ground.” That sense of accomplishment she must have felt in not just owning a home, but also having her own production facility “on her own ground” must have been immensely satisfying (I must add that Walker’s great-granddaughter A’Lelia Bundles wrote an excellent book about her life and called it On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker).

From Indianapolis, Walker’s business only continued to grow exponentially. Her daughter convinced her to expand the business to New York in 1913, where they settled in Harlem. Walker soon bought a rowhouse at 108 West 136th Street in Harlem in 1913, and bought its adjacent neighbor at 110 two years later. And while Malone may not have been able to find a Black architect to build her Black-focused beauty campus, Walker did not have the same issue. She and A’Lelia sought out Vertner Woodson Tandy (1885-1949), the most prolific Black architect and the first registered Black architect in New York, for the design and construction of what was then the most iconic and significant building of their business.

The exterior of the Tandy-designed townhouse at 108 and 110 West 136th Street, circa 1916. Byron Company (New York, N.Y.) Museum of the City of New York. 93.1.1.10838.

The rowhouses were originally two adjacent brownstones constructed in the 1880s; Tandy renovated the two rowhouses into a single, sprawling mansion that housed A’Lelia’s residence on the upper floors and a salon and training center on the lower floors. Rather than retaining the original brownstone facades — they would have been deemed passée and old-fashioned by then — Tandy gave the front facade a Neo-Georgian makeover, with red brick and limestone and a rounded bay window. The facade was well-composed, with a limestone base, arched window enframements on the second floor, and a tall, prominent cornice that rose above its dreary neighbors. The public-facing interiors were light, bright, and plant-filled (one can imagine being perched on the poufy settee expertly wrapped around a column!); the upper floors were outfitted with large tapestries, a grand piano, and lots of wall paneling. It’s possible that the interiors were designed by the decorating duo Righter & Kolb, who had designed several other wealthy New York homes. Altogether, the exterior and interiors gave a sense of refinement, wealth, and comfort..

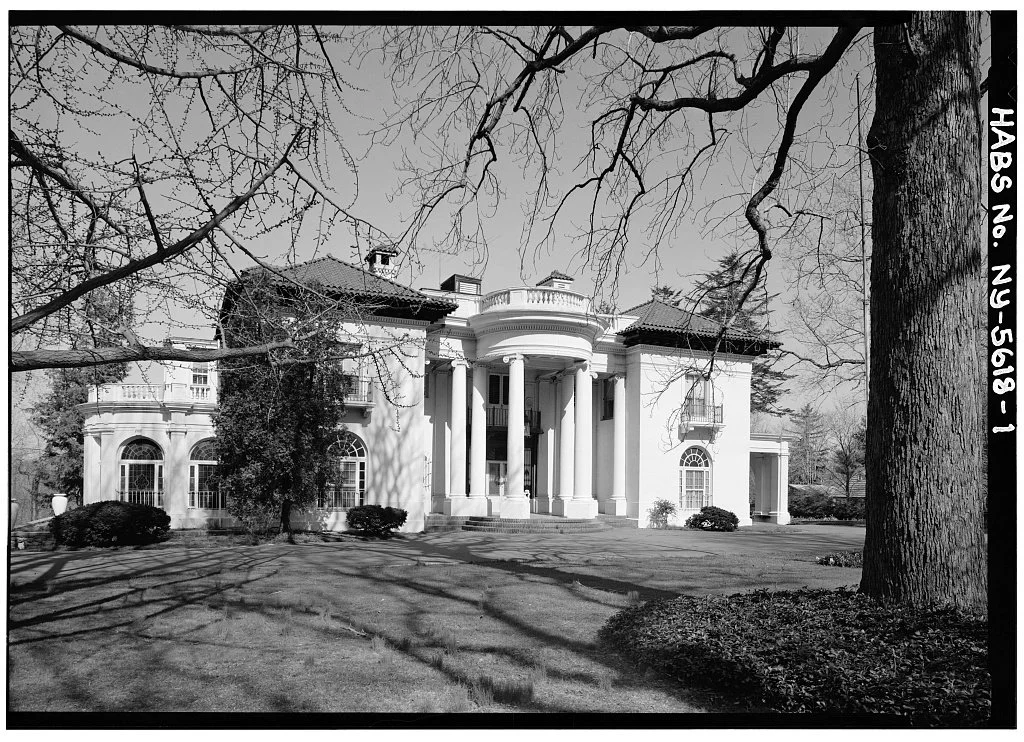

When Madam C.J. Walker decided to move to the Westchester County of Irvington (her daughter A’Lelia was more of the city girl and stayed in Harlem), Walker again hired Tandy to design her three-story, 16,000 square-foot, 34-room Italian Renaissance-style mansion — ahem, villa. The home, described in 1917 by the New York Times as furnished with “a degree of elegance and extravagance that a princess might envy,” was filled with bronze and marble statuary, cut glass candelabra, paintings, and a gold-plated piano (I’m speechless).

But despite her wealth, the local community (with its own crew of millionaires) did not accept Walker with open arms at her Irvington palace, which she called Villa Lewaro (for A’Lelia Walker Robinson, her daughter’s married name). The Times gossiped about the neighbor’s shock when they realized who was building a home in their prized neighborhood: “On her first visits to inspect her property the villagers, noting her color, were frankly puzzled. Later, when it became known that she was the owner of the pretentious dwelling, they could only gasp in astonishment. ‘Impossible!’ they exclaimed. ‘No woman of her race could afford such a place.’”

East Elevation of Villa Lewaro, North Broadway, Irvington, Westchester County, NY. C. 1987. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Part of HABS NY,60-IRV,5.

Satisfyingly, Walker more than afforded it — she relished the home, hosting dozens of high-profile events in the ensuing decades (take that, snooty, racist neighbors!). Like Malone, both her Harlem residence and Villa Lewaro were literal hair salons but also salons in the French Enlightenment sense, where political organizing, philanthropy, and cultural leadership took place. The Harlem residence was initially known as the Walker Studio and later the Dark Tower (after a Countee Cullen poem), where lavish parties were attended by the greats of the Harlem Renaissance: W.E.B. Du Bois, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and more. Indeed, in Hughes’ 1940 autobiography, he described the townhouse as a place that could hold about a hundred people, so jam-packed once the party got started that it was “as crowded as the New York subway at the rush hour” (important difference: people seemed to enjoy getting squished).

Villa Lewaro events in the late 1910s through the 1920s ranged from NAACP commemoration events to recordings by Langston Hughes to the National convention of Walker beauticians (historian and educator Dr. Tara A. Dudley does a fantastic job of noting some exceptional events in her piece “On Madam C. J. Walker’s Architecture” in Black Perspectives).

Unfortunately, Walker died unexpectedly less than a year after the completion of Villa Lewaro in 1919; A’Lelia took over the business, but she too passed away in 1931. The Depression years were not kind to the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, and Villa Lewaro was sold after A’Lelia’s death. The contents of the home were auctioned off (newspaper articles mention 800 attendees at the auction, including “"Madam Walker's white neighbors, who resented her presence in the quiet Westchester town,” commented The New York Amsterdam News in 1930). The rowhouses in Harlem were leased to the City and turned into a health care clinic triage facility; they were ultimately demolished in 1941 and replaced with the Countee Cullen Branch of the New York Public Library.

Ground Floor of 108-110 West 136th Street, c. 1915. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

Today, however, some of Walker’s real estate and architectural legacy remains and is honored. Villa Lewaro, for example, is today a National Historic Landmark, and has had the benefit of only a handful of owners, many of whom deeply appreciated its significance to the Black community, including the NAACP (dare I mention a big, colorful spread in Ebony in 2008, a very glamorous Essence magazine photoshoot in 1995 with the Doley family, who lived there in the 1990s and 2000s, and over a dozen other major articles in national publications?).

A'Lelia's room on the upper floors of 108-110 West 136th Street, c. 1915. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

Today, it’s owned by the non-profit New Voices Foundation. While Walker’s home at 640 N. West Street in Indianapolis was demolished and is today an apartment building, it’s just down the block from a multi-use commercial and headquarters facility built in Indianapolis in 1927 by A’Lelia (and to the designs of local architects Rubush & Hunter, who were not Black, in case you were wondering). The four-story, African-Art Deco building is now called the Madam Walker Theatre Center and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1991.

It’s clear that for both Walker and Malone, real estate and design were inextricably connected to success and public perception. Just as women, especially Black women, of their era were judged by their appearance (okay, still happens today!), so too were their businesses. Their real estate holdings not only gave them financial security, but also a physical presence in their communities that bolstered their business credo and gave their communities a place to gather, meet, discuss, and learn.

Ownership of these buildings must have also had deeper meaning. Can you imagine how it must have felt to look around a luxurious home like Villa Lewaro or a bustling beauty school and think, I own all this — and only a generation ago, someone owned my parents and my siblings? It must have been such a remarkable, unforgettable (but not, as Walker’s neighbors thought, “impossible”) feeling that both Walker and Malone felt needed to be shared, celebrated, expanded, and proliferated. Land ownership became a form of defiance, asserting what their ancestors had been denied, while also laying the groundwork for generational wealth and community economic mobility. And while most of the built legacies by Malone and Walker do not survive, the few that endure still bear witness to their stories.

Additional Reading:

The depth and breadth of existing scholarship on these two women, particularly from recent years, was striking. Below is just a sampling of what is out there for more reading:

“Annie Malone and Poro College: Building an Empire of Beauty in St. Louis, Missouri from 1915 to 1930” by Chajuana V. Trawick, dissertation at the University of Miami.

“Sharing an Awe-Inspiring Story” by by James Agbara Bryson in Peoria Magazine.

Story of Pride, Power, and Uplift: Annie T. Malone (The Great Heartlanders Series) by J. L. Wilkerson.

Gospel of Giving: The Philanthropy of Madam C. J. Walker, 1867-1919 by Tyrone McKinley Freeman.

In Her Place: A Guide to St. Louis Women’s History (Volume 1) by Katharine T. Corbett.

Discovering African American St. Louis: A Guide to Historic Sites by John A. Wright.

Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America by Ayana D. Byrd & Lori L. Tharps.

Styling Jim Crow: African American Beauty Training during Segregation by Julia Kirk Blackwelder.

On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker by A’Lelia Perry Bundles.

Beauty Shop Politics: African American Women’s Activism in the Beauty Industry by Tiffany M. Gill.

African-American Business Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary by John N. Ingram & Lynne B. Feldman

Permanent Waves: The Making of the American Beauty Shop by Julie Willett

Robert O. French Papers archival collection at the Chicago Public Library

Madam C.J. Walker Papers at the Indiana Historical Society

“Seeking the Ideal African-American Interior: The Walker Residences and Salon in New York” by Tara Dudley in Studies in the Decorative Arts

“Hair Care Helped a Community: Black Entrepreneur Annie Malone and Poro College” by Zubin Hill for the National Trust for Historic Preservation

“How A'Lelia Walker And The Dark Tower Shaped The Harlem Renaissance” by Lauren Walser for the National Trust for Historic Preservation

“On Madam C. J. Walker’s Architecture” by Dr. Tara A. Dudley in Black Perspectives

“Affluence and Community at the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company” by Paul R. Mullins in Black Perspectives