A Day Among the Thermal Pools of Iceland with Sím Residency and RISD's Debbie Chen

Debbie in her studio at the Sím Residency in Reykjavik.

Debbie Chen is Assistant Professor in Architecture at Rhode Island School of Design. Working in the overlap of infrastructure and architecture, her projects offer alternative forms of utility that prioritize cultural production and environmental kinship. In pursuit of infrastructural intimacy, she is currently designing a series of water and energy infrastructures that foreground ritual-making and recreation.

Debbie is currently taking a semester-long research leave as an artist-in-residence at the Sím Residency in Reykjavik, Iceland. She intends to study the relationship between geothermal energy and Iceland’s rich bathing culture.

As a licensed architect, Debbie previously served as Project Architect at Morphosis Architects, where she also worked on infrastructural projects. Prior to joining RISD, she taught at Syracuse University and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where she was the 2021-2022 Architectural Activism Fellow.

7:00am: My phone alarm goes off and I immediately miss my sunrise alarm clock back home. I’ve always been a light-dependent sleeper so spending the winter in Reykjavik, where the window of daylight is short, has taken a huge mental adjustment. Currently, the sky doesn’t brighten until 10:00am.

I stay in bed and warm up mentally. The first thing I think about is my running workout for the morning. I’ve recently started my training block for the London Marathon so I check the targeted pace and distance of the workout with the current weather forecast to plan my route. I started long-distance running eight years ago when I was working in construction administration for a large multi-year government project. I found that the small incremental gains of building architecture synchronized well the steady rewards of training for a large goal, like a marathon. Now, I always start my day with a run to feel connected to my body and to the outdoors.

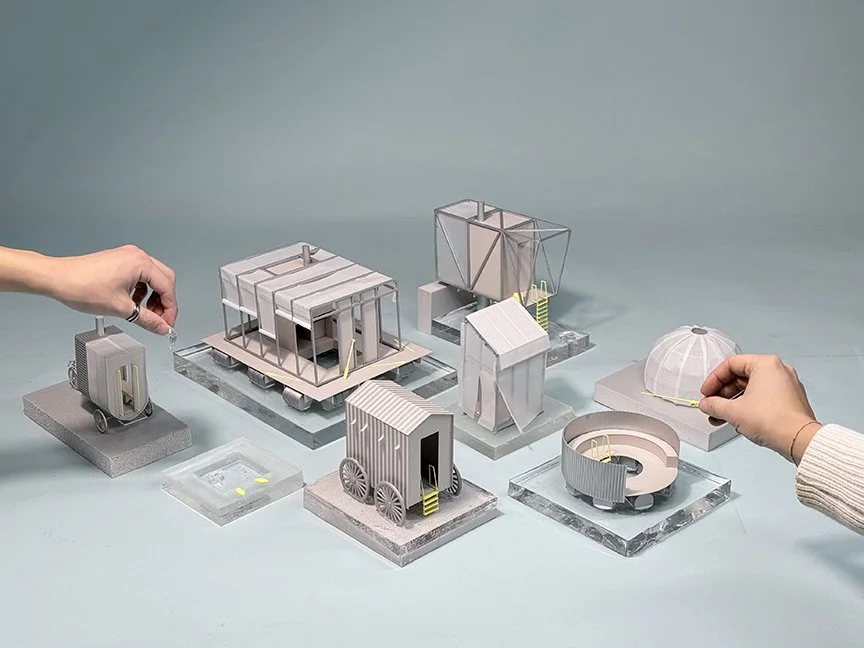

At RISD, Debbie has been working with graduate students on designing bathing typologies that foster dependency on solar energy. Photo courtesy of Debbie Chen.

7:30am: I warm up — I put on my running clothes and go through a series of exercises. The weather in Iceland can change very quickly. High winds and icy roads are making me appreciate slowness and prudency.

8:00am: I finally step out and hit the pavement. My weekday runs are usually thirty to sixty minutes long. I enjoy running up and down the western coast from Grandi to Seltjarnarnes since its well-lit and equally suitable for easy and speed workouts. On the days that I run late enough to catch the daylight, I soak in the view of Mount Esja to the north.

9:00am: After finishing my run, I spend a few minutes evaluating my progress, logging the activity, and checking in on my running friends via Strava. Then I shower, get ready, and eat a quick breakfast. Usually, I’ll spend the day between going to the city library and working in my studio space at the residency. But today, I’m driving out east with a fellow resident to visit a few noteworthy thermal pools.

10:00am: We take off in the rental car and make our way out of Reykjavik in the twilight. Our first destination is Seljavallalaug, located along the southern coast. The drive takes two-and-a-half hours and we pass through beautiful expanses of farmland, with sprinkles of Icelandic horses, as the sun slowly rises to meet us from the east.

Debbie hiking into the Reykjadalur Valley to visit the Hot Spring Thermal River. Photography by Luna Van Der Straaten.

12:30pm: We peel off of the Ring Road and drive up a secondary road for three kilometers before parking in a gravel area. Then we grab our rain shells and prepare to hike into the valley to find the pool. Hiking to a bathing site is like icing on the cake – we recently visited the Reykjadalur Hot Spring Thermal River and the windswept pilgrimage into mountain valley rewarded our pursuit with a restorative soak in warm waters.

1:00pm: After thirty minutes along the Laugará river, we spot a hot water tank. I’m excited to visit Seljavallalaug not only because of its unique siting along a cliffside, but also because of its historical significance in Icelandic bathing culture. Before the 1900s, not many Icelanders new how to swim despite the country’s increasing investment in the fishing industry. To prevent drowning and promote physical wellbeing, youth clubs started building swimming pools, often warmed by hot springs, and offering swimming lessons.

Built by the Eyjafjöll Youth Association in 1923, Seljavallalaug and its local council became the first in Iceland to require children to learn to swim. I’m intrigued by this overlap of public governance, infrastructural development, and recreational space — Seljavallalaug offers an inspiring case study for how small moments of infrastructural design can foster cultural practices.

Seljavallalaug, the first public pool to implement required youth swimming lessons in Iceland, nestled into the side of the Eyjafjöll mountains. Photography by Debbie Chen.

I study and document the water tank which appears to be collecting hot water runoff from the cliffs. A pipe from the tank leads us to the pool with one side nestled into the cliffside. I take note of how simply the pipe terminates over the edge of the open-air pool to supply a steady flow of hot water and I take photographs of various details including the concrete changing structure, the outflow valve at the bottom of the pool, and the metal ladders. In the interest of visiting other sites, we decide not to swim in Seljavallalaug and hike back to the car. On the way back, we encounter a handful of teenagers with swimsuits and towels.

2:00pm: Back in the car, we eat some sandwiches and snacks we packed for the trip before setting out to our next destination, Hrunalaug.

2:30pm: Within twenty minutes, we make an impromptu pit stop at Seljalandsfoss, a breathtaking waterfall right off of the Ring Road. We take some photographs, feel the cold spray on our faces, and indulge in a hot chocolate for the road.

Hrunalaug hot spring, near the village of Fluðir. Photography by Debbie Chen.

4:00pm: We arrive at Hrunalaug just in time for the sun to start setting. Built around 1890 by farmers of Ás, the thermal pools of Hrunalaug were originally used for laundering and bathing. I’m delighted to learn that the pitched roof structure was added in 1935 to bathe sheep. The thermal pools are fed by rainwater warmed by naturally hot rock formations. Like other idyllic thermal baths in Iceland, Hrunalaug has undergone major improvements in the last decade due to increased tourism.

After a quick walking tour around the site, we chat with the pool attendant and she describes the new changing facilities under construction. Then we change into our bathing suits and try out the various pools. The pools accommodate four to eight people and are lined with river stone, but there is a small concrete cistern right in front of the little sheep hut that you can fully immerse your body in. We spend most of time in the largest and warmest pool, looking at the sun set in the valley beyond.

5:00pm: Before the sun fully sets, I change and take a quick round of photographs before returning to the car. We feel ambitious in our itinerary so we decide to visit one last pool, the Secret Lagoon, which is only five minutes away from Hrunalaug. Both pools are located in the same geothermal area.

5:15pm: We check in to Secret Lagoon and proceed through the showering etiquette before taking a dip. This pool is a good case study for natural thermal pools that hold on to their rustic character. The Secret Lagoon, or Gamla Laugin, is actually the oldest pool in Iceland. Built in 1891, it was the first pool to offer swimming lessons in 1909. As with other community pools, Gamla Laugin became a hub for social activity in the community.

By now the sun has set and bathing in the evening offers a different experience. The water in Gamla Laugin is warmer than other pools we’ve tried, given its immediacy to nearby geothermal activity. The evaporation from the warm water as it hits the cold night air heightens the relaxing atmosphere. After some time in the large pool, we go through a few cycles in the cold plunge. Lastly, I take a stroll along the boardwalk to admire the active geothermal areas directly feeding the pool. The original concrete and stone changing structure is still intact.

7:00pm: We leave Secret Lagoon and head back to Reykjavik.

Northern lights spotted outside of Selfoss.

7:30pm: Outside of Selfoss, we’re treated to an encounter with the Northern Lights. I stop at a gas station and we run across the street to take the photographs. I had been waiting to see them this clearly since arriving in Iceland three weeks ago.

9:00pm: We finally arrive back at the residency and make dinner. Luckily, I have leftovers. As we prepare our meals, we check in with other residents to see how their days went and give them a recap of our trip. It’s been inspiring to learn about other people’s creative practices while here in the residency. We’re all pursuing different interests but are finding commonality in the shared inspiration from this landscape.

10:30pm: My work is often grounded in the practical aspects of infrastructure, climate change, and public policy so I like to end the day with a bit of contrast and relief by reading fiction. These days, I’m enjoying What We Can Know by Ian McEwan, which tells a futuristic story of climate change, but through the irreducible complexity of human relationships.

11:15pm: After a good day of driving and soaking, I’m ready to drift off to sleep.

This piece has been edited and condensed for clarity.