A Boston Marriage, An LGBTQIA+ Design Pioneer: Interior Decorator Elsie de Wolfe

Bessie Marbury and Elsie de Wolfe, from Elisabeth Marbury's My Crystal Ball, 1923.

By Kate Reggev

A special thank you to Sarah Nelson-Woynicz for acting as a reader for this piece.

In recent years, history (and the broader population) has increasingly brought visibility to LGBTQIA+ narratives and stories, including in the architecture and design worlds. Grassroots organizing in the design world emerged in the 1990s: the Organization of Lesbian and Gay Architects and Designers (OLGAD) was established in New York City in 1991, the Boston Gay and Lesbian Architects and Designers (BGLAD) was formed as a committee of the Boston Society of Architects in the 1990s, and Gays and Lesbians in Planning (GALIP) was created as a division of the American Planning Association (APA) in 1992. By the time architect Philip Johnson appeared on the cover of Out magazine in 1996, LGBT was officially part of the design conversation.

It took another decade or two, though, for recognition at the local, state, and federal levels. In 2015, the Stonewall Inn was declared a New York City Landmark (although it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 2000); states and cities established LGBTQIA+ national marker programs and public art projects; and in 2016, the National Park Service established an LGBTQ Heritage Initiative.

And yet while all of this might seem relatively recent (okay, yes, the 1990s were 30 years ago, but still! We’re looking at the long timeline of history here), there is a deep, complex history of the LGBTQIA+ community’s impact on and contributions to the architecture and design community. However, this history has often given more visibility to those who are cisgender and gay men, and downplayed, ignored, or passed over the history of LGBTQIA+ women.

Interior of their home on Irving Place, from Elsie de Wolfe's The House in Good Taste, 1913.

As early as the turn of the twentieth century, there is documentation of women who were, to varying extents, open and public about their sexual orientation and life partners, and yet still active and highly respected within the design and architectural communities. Examples include the brilliant Irish early Modernist Eileen Gray (1878-1976); the flamboyant Elsie de Wolfe (1859-1950), broadly considered the first professional interior decorator (and the primary visionary that we’ll discuss today); Virginia-based architect and educator Amaza Lee Meredith (1895-1984 — who we’ve previously discussed here); and the perhaps lesser-known but still prolific Boston-based architect Eleanor Raymond (1888-1989).

But first, it’s important to point out that researching LGBTQIA+ history shares many of the same challenges as other historically marginalized and underrecognized communities — but to an extreme: it typically consists of narratives that were intentionally hidden, contested, obfuscated, actively disguised, erased, or ignored, often both as they were happening and also over time by others who studied them. And when it comes to researching the history of LGBTQIA+ women architects and designers within the LGBTQIA+ community, it’s even more challenging — basically a marginalized double-whammy (ahem, my own technical term, better known as intersectionality). As Megan E. Springate noted in her 2017 essay “The National Park Service LGBTQ Heritage Initiative: One Year Out,” "Much of the popular narrative around LGBTQ history focuses predominantly on the history of white, urban, middle-class, cis-gender gay male experience. Missing are the histories of transgender folk, lesbians, bisexuals, people living in rural areas, and people of color."

Then, of course, there’s also the question of terminology. Historian and preservationist Jay Shockley noted in a 2018 interview, “Terminology about sexuality and gender has continually evolved. ‘Heterosexual’ and ‘homosexual’ is late 19th century. ‘Bisexual’ and ‘transgender’ only started developing in the 20th century and have been used in different contexts for different things. Some people have said: ‘How can you call someone living in the mid-19th century a lesbian? That term didn’t exist then.’”

To Shockley’s point, a “Boston marriage,” for example, was a relatively established tradition in the 19th century that usually implied romantic but not sexual relationships between two women living together; however, by the 1920s, this concept had changed and the term was often known, even sometimes accepted, that two unmarried women living together might very well be lesbians.

Indeed, one of the best-known “Boston marriages” at the turn of the 20th century in New York was the dynamic duo of former actress Elsie de Wolfe and trailblazing female theatrical agent Elisabeth "Bessie" Marbury. The two met through New York’s theater community in the 1880s, and by 1892, de Wolfe was openly living with Marbury, first near Union Square at 122 East 17th Street at Irving Place (“a quaint mansion,” she called it) and later uptown at 13 Sutton Place.

De Wolfe became interested in decorating through set design during her time as an actress, and she delved into the field in the late 1890s when she redecorated the interiors of No. 122. Within a few years she deemed decorating her true calling and retired from the theater (perhaps for the best — many, with the exception of Marbury, described her talents on stage as loosely mediocre). Soon, she was busy establishing her design vision that contrasted sharply from the typical interiors of the day (think traditional Victorian-era design, with heavy velvets, wood paneling, and lots of William Morris wallpapers in deep greens and browns). In fact, she described herself as “a rebel in an ugly world” (and yes, that was in fact the title of a chapter in her 1935 autobiography, After All), revolting against the aesthetic norms of the day. She embraced an emphasis on lightness and intimacy, employing wicker, tiled floors, trellises, mirrors, light-colored fabrics, and plenty of eighteenth century French furniture to create spaces that were distinct, delicate, and clearly de Wolfe.

De Wolfe’s career really kicked into high gear in 1905 when Marbury and close friend Anne Tracy Morgan (daughter of J. Pierpont Morgan), along with Stanford White (of the legendary architecture firm McKim, Mead and White), helped her secure the commission for the interior decoration of the Colony Club, the first social club established in New York City by and for women. With her signature interiors, the Club — and de Wolfe — became a huge success.

Soon, de Wolfe was the most sought-after interior decorator on the East Coast, with clients ranging from elite private clubs and prominent businesses to notable educational facilities and lavish mansions of the early twentieth century at a time when the concept of an interior decorator, especially for women, was novel. Indeed, interiors, in particular public spaces, were typically executed only by male architects or antiques dealers. By the 1920s, her client list included Henry Clay and Adelaide Frick, Anne Harriman Vanderbilt, Anne Morgan, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, among others.

Yet equally as exciting as her design commissions was her social life, which was widely written about in various publications at the time — The Times called her "a social leader on the Riviera” and an “international hostess” in her obituary in 1950; in 1935 (at age 70! In the middle of the Great Depression!) she was named by Parisian dressmakers as “the best-dressed woman in the world” (note to self: exclusively wear handmade French ensembles and you could achieve this title too). A 1938 profile on her in The New Yorker detailed her and Marbury’s Sunday teas with literary greats such as Oscar Wilde, Mrs. Humphry Ward, and Sarah Bernhardt and socialites Henry Adams, Mrs. William Waldorf Astor, and Edith Wharton. The article also noted Marbury and de Wolfe’s decades-long friendship with Anne Tracy Morgan, daughter of J. Pierpont Morgan, and her lover (and widow of William K. Vanderbilt) Anne Vanderbilt.

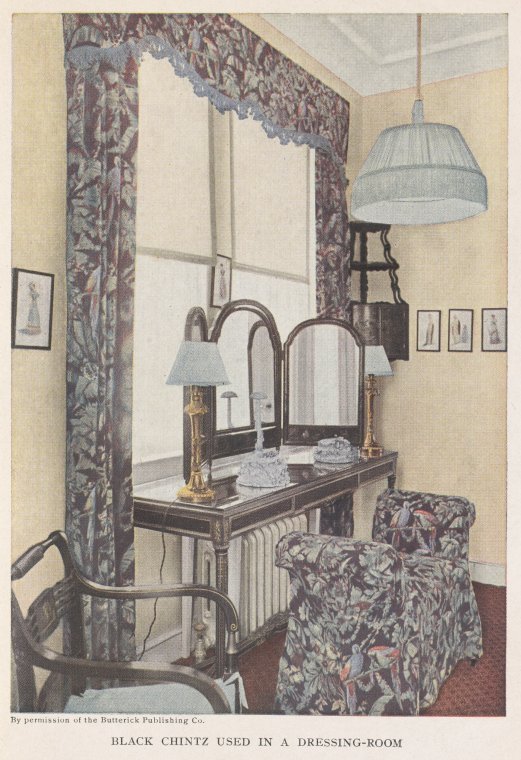

Black chintz used in a dressing-room designed by Elsie de Wolfe, published in The House in Good Taste, 1913. Courtesy of NYPL.

Significantly, it was publicly known and, at least to some degree, accepted by their peers in high society that Marbury and de Wolfe lived together and were in a long, serious relationship together. Publications across the nation frequently noted their travels together, cohabitation at Irving Place in the winter, and summers together at their home in Versailles, France (fear not, de Wolfe also expertly decorated this home as well). An 1894 Chicago Daily Tribune article described them as “girl bachelors” living together, and noted “it is not often two women live together who bear no relation toward each other, and yet share all the pleasures, trials, and struggles of life in harmony.” The article detailed the design of their Irving Place residence, and ended with a description of their living arrangement: “boudoirs” separated by a “narrow hallway.” I have to wonder: was it a subtle reference to their romantic and sexual relationship, or simply an explanation of the layout of the home? May I also add — for color (no pun intended!) — that the color scheme for de Wolfe’s bedroom was "pink and delicate mauve," and that "at the foot [of the bed] rests a lounge covered with a fur rug." Cozy! Timeless! Instagrammable!

Not only were newspapers and magazines writing about them — in fact, the two appeared in newspaper articles so often that one wonders if newspaper columnists were also guests at their Sunday teas — but also the couple was somewhat explicit about their relationship in their own writings. In her1913 book The House in Good Taste and her 1935 autobiography After All, de Wolfe referred to Marbury as “my friend” and their “great and enduring friendship,” and Marbury dedicated her 1923 autobiography, My Crystal Ball, to “her friend” Elsie de Wolfe. Their relationship, per Marbury, was “intimate” and described as "a friendship that...has remained unbroken and inviolate" over the decades.

With that in mind, you can imagine that it was news to many — quite literally, it made the first page of The New York Times — when de Wolfe married diplomat Sir Charles Mendl, a British press attaché living in Paris, in 1926. Today, historians point out that the relationship appeared to be platonic and for social reasons; in fact, de Wolfe barely mentioned him in After All. Even the Times announcement commented, “"When in New York she makes her home with Miss Elisabeth Marbury at 13 Sutton Place,” suggesting that despite the marriage, the relationship between the two women would likely continue.

It’s difficult to confirm if this is true, but there are a few hints: in May 1926, a few months after de Wolfe’s marriage, the Times mentioned her arrival in New York from France the same week that actress Carlotta Monterey, who had been staying for several months with Marbury, would be leaving Marbury’s residence. The timing seems uncanny, but it’s not explicit. Later society notes in newspapers into the late 1920s and early 1930s note when de Wolfe arrived in New York and stayed with Marbury at the residence on Sutton Place, and continued to call de Wolfe Marbury’s “inseparable companion,” along with Anne Morgan. Marbury threw dinners and teas in the new Lady Mendl’s honor when she was in town, and it’s clear that their relationship continued to some extent. Ultimately, in 1933, when Marbury passed away at age 77, de Wolfe was the primary beneficiary of her will.

On the one hand, it can be difficult to square the rigidity and expectations of gender and sexuality of the Victorian era with the seemingly lively, bohemian, yet well-respected lifestyle the two led. How were both Marbury and de Wolfe able to become extremely successful in their respective fields, in spite of their personal lives, which were so frequently broadcast across the nation and the world? Was society at the turn of the 20th century really more open and accepting than previously thought? Is it possible that their talents overshadowed what might have otherwise been seen at the time as unacceptable romantic lives?

On the other hand, though, I would suggest that the key to answering this question is to look at the society that Marbury and de Wolfe came from and the circles they moved within. Both benefited from coming from white, upper class families — Marbury in particular came from a wealthy, long-standing family in New York — and started out life with many connections that would help propel the two forward. While money cannot buy happiness, as the adage goes, it can definitely make life easier and enables one to make choices that might lead to happier circumstances, like being able to choose your friends, where you live, and how you spend your time. Perhaps the couple were selective with whom they socialized, and intentionally moved within more accepting artistic circles filled with writers, designers, and others who might follow a less orthodox life helped as well.

Then finally, I also wonder if there’s something related to the ideas of exceptions (of their time) being easy to accept, since they’re seen as novelties and one-offs. We’ve noted in previous articles that sometimes a singular exception to a rule, like one woman in an architecture class, isn’t protested against — it’s when the number of women in the class feels threatening to the status quo that it becomes, in the eyes of some, a “problem.” Perhaps de Wolfe was viewed by others as a splashy, exciting figure who was perhaps just as entertaining, if not more so, in real life than when she was on the stage.

Regardless of how she was perceived during her lifetime, de Wolfe was able to meaningfully alter the perception of interior decoration and used her status to blaze a trail for women in the design world. She noted in After All that "I do feel that my first, timid plunge into the field of interior decoration opened up a new and satisfying career for women.” And even though it may not have been her primary intention, she also paved the way for LGBTQIA+ members of the design community and their own unique voices.

Curious for more? Resources:

Alex D. Ketchum, “Lost Spaces, Lost Technologies, and Lost People: Online History Projects Seek to Recover LGBTQ+ Spatial Histories,” Digital Humanities Quarterly; Providence Vol. 14, Iss. 3, (2020).

Arica L. Coleman, “What's Intersectionality? Let These Scholars Explain the Theory and Its History,” Time, March 28, 2019.

Edgar Munhall, Elsie de Wolfe: The American pioneer who vanquished Victorian gloom, Architectural Digest, December 31, 1999.

Elisabeth Marbury, My Crystal Ball: Reminiscences, London: Boni and Liveright, 1923.

Elsie de Wolfe, The House in Good Taste: Design Advice from America's First Interior Decorator, New York: Century Company, 1913.,

Elsie De Wolfe, After All, New York: Arno Press, 1935.

Erin Blakemore, From LGBT to LGBTQIA+: The evolving recognition of identity, National Geographic. October 19, 2021.

Janet Flanner, “Handsprings Across the Sea,” The New Yorker, January 7, 1938.

Katherine Crawford-Lackey and Megan E. Springate, editors. Preservation and Place: Historic Preservation by and of LGBTQ Communities in the United States. New York: Berghahn Books, 2019.

N. Chloé Nwangwu, “Why We Should Stop Saying “Underrepresented,” Harvard Business Review, April 24, 2023.

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission Designation Report, East 17th Street/Irving Place Historic District, 1998.

Peter Dedek, The Women Who Professionalized Interior Design, New York: Taylor & Francis, 2022.

Tatum Alana Taylor, “Concealed Certainty and Undeniable Conjecture: Interpreting Marginalized Heritage” (Masters thesis, Columbia University, 2012).