“Dared to Enter”: Black Female Architects and Their Architecture Education

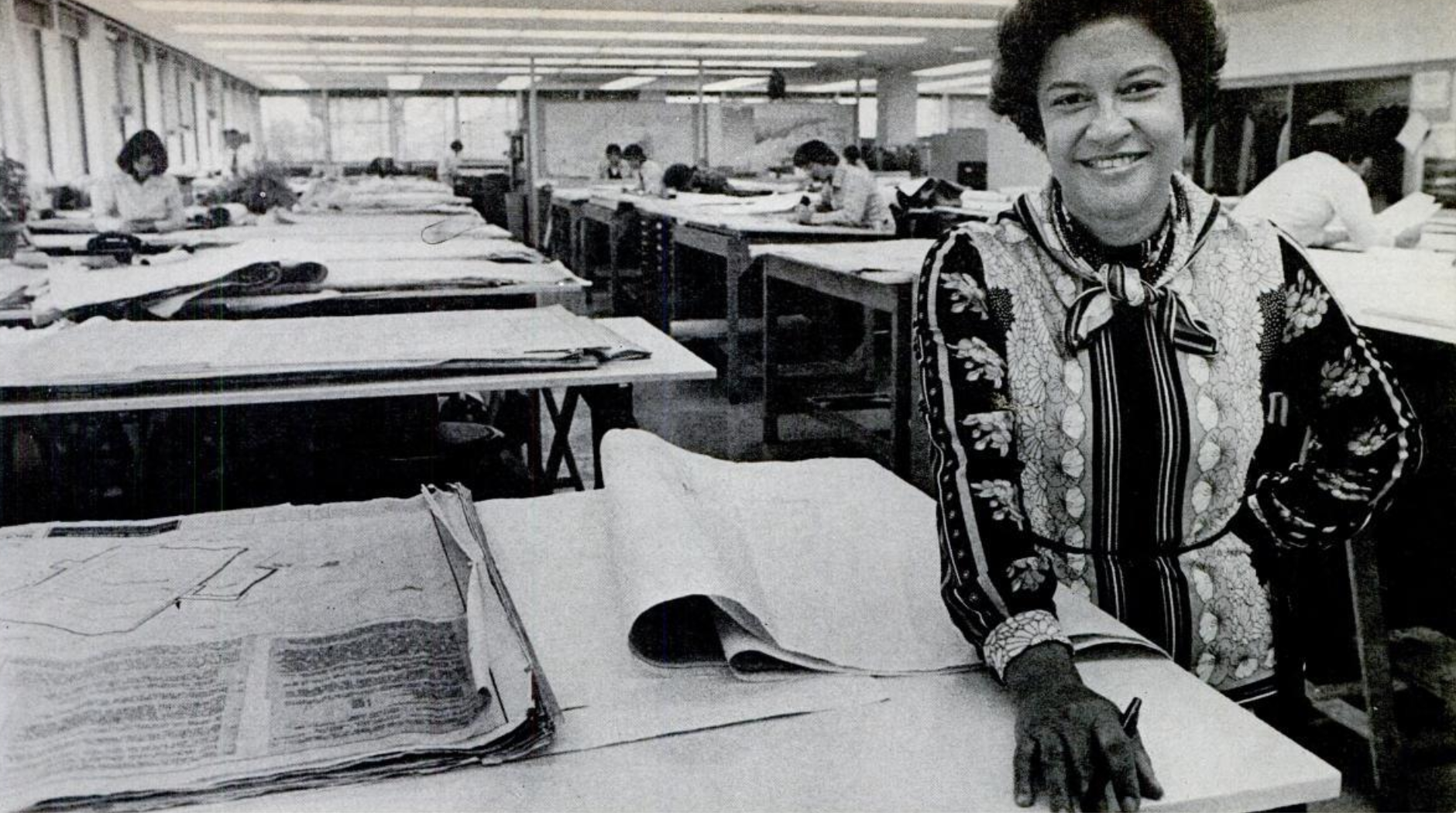

Norma Sklarek in Ebony, August 1977.

By Kate Reggev

In 1983 (exactly 40 years ago!), a one-day conference was held at Howard University. Titled “Minority Women in Architecture: A Sense of Achievement”, it brought together about 100 Black female architects, architectural designers, and students from around the country and was a space to celebrate, commiserate, learn, and uplift.

At the time, there were fewer than 200 Black female registered architects (refresh: in 2020, we passed over 500 — woohoo! — although as of 2022 NCARB still states that “Black or African American women continue to make up less than 1% of the total architect population in the United States”). At the conference, Toni R. Cook, then-associate dean of Howard's School of Architecture and Planning, noted that only about 8 Black female students graduated from NAAB-accredited schools each year. However, she also asserted that the number would be closer to 2 students if it weren’t for the likes of schools like Howard, Hampton Institute, Tuskegee Institute and Southern University.

So here on In Ink, I wanted to spend some time diving into what architecture school must have been like for these women who attended the conference, and more specifically at these schools that contributed a (relatively) higher number of Black females to the field. School is such a foundational (no building-related pun intended!) period for architects and designers, shaped by our experiences in studio as much as they are out of the classroom and by professors just as much as our peers next to us (I think we all know who we learn basic rendering settings or all of the Illustrator shortcuts from, and it’s not our critics!).

Architecture student Garnett Katherine Keno, a member of the Bison yearbook staff, at Howard University in 1953. Courtesy Howard University Yearbook, 1953.

It is broadly known that Black people were largely barred from higher education in the United States before the 19th century, and as a result what we now call historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) were established, often in the South. These schools were specifically formed to educate Black Americans, and so at the schools that Cook mentioned — Tuskegee, Howard, Hampton, and Southern — one might think that the “double-whammy” of challenges Black women faced (being both Black and female) would be simplified, maybe even halved; in theory in these environments, Black women studying architecture would be unique due only to their gender rather than also because of their race.

Several of these schools even have a long history of educating women: Howard University and Tuskegee University (originally called Tuskegee Institute) proudly produced female graduates as early as 1872 and the 1880s, respectively. In fact, by 1896 there were already a whopping 38 women on the faculty and staff at Tuskegee, reflecting the school’s ideals of crafts, industrial and farming skills, and hands-on experience.

But… sigh. There always seems to be a “but”! Exciting as these numbers are, the early female Black graduates at these schools studied English, social sciences, and even medicine — that is to say, a range of subjects, but not architecture. Somewhat shockingly to me, the first female architecture students at these schools didn’t emerge until the 1930s at Tuskegee and the 1950s at Howard (Alma Murray Carlisle and Nada Jones Williams) — the same time Black female students entered other land-grant and private universities like Cornell (1940s with Alberta Cassell and her sister Martha Cassell Thompson) and Columbia (1950 with the illustrious Norma Sklarek), and decades after white female students entered these schools. In short, Black female students enrolled in architecture programs approximately the same time regardless of whether they were attending an HBCU or a largely white institution. The reason why there were no conferences for Black women in architecture before the 1980s was because, frankly, before midcentury, there were virtually no Black women in the field who had completed a formal education.

Architecture class at Tuskegee, 1971. Courtesy of Tuskegee Yearbook, 1971.

I think there’s a few reasons for this. One is my underestimation of the power of gender dynamics until the mid-20th century and afterwards (dare I even say… until today?). As the pioneering Black female architect Norma Sklarek noted at the conference in 1983, “"Prejudice is mostly focused against women, period. Being black adds another dimension, and upward mobility and advancement may be the most difficult problem black women architects may face." For Norma, her primary obstacle was actually her gender, not her race -- which might explain why black women began attending architecture schools at roughly the same time whether they were HBCUs or not.

Another reason for this might also be due to the pedagogy of the schools, particularly in the case of Tuskegee. The school was known for a more industrial, practical teaching methodology following the ideals of its founder Booker T. Washington, and the master builder program (the precursor to the architecture program) emphasized apprenticeships and on-site construction experience — spaces that were generally seen as inappropriate for women because of their very physical nature and associations with manual labor. We’ve talked about how many felt that if women were to practice architecture, it should be to design residential environments like homes — spaces that women “intrinsically” knew. If that were the case, construction sites and apprenticeships where women would, for example, make bricks and then set them as masons would most definitely not fall in the realm of accepted spaces for most women — Black, white, or otherwise.

In fact, at Tuskegee, the architecture and master builder program appears to have not have even permitted women until the 1930s, at which point the architecture department was reevaluated and remodeled after the “traditional” approach at that emphasized drawing and designing, explains Carla Jackson Bell, Ph.D (herself the first female tenure-track professor at Tuskegee in 1991). Indeed, as former librarian at Tuskegee and Auburn University Vincent McKenzie noted, after the school opened the architecture program to women in 1933, four women enrolled in the following semester: Virginia Adams-Driver, Cornelia Bowen, Ellen McCullough, and Alice Torbert-Scott.

Frances Benjamin Johnston, courtesy Library of Congress Roof construction by students at Tuskegee Institute, c. 1902.

Frustratingly, I have not been able to find any additional information about any of these women, although two share names with prominent early graduates of Tuskegee who opened public schools in rural areas for Black Americans in the 1890s. Is it possible that they previously attended Tuskegee, established these rural public schools, and then three or four decades later went back to school for architecture? It feels… unlikely, to say the least, but it’s possible there is some kind of family connection.

Regardless, between 1933 and 1967, no women actually graduated from the program, and by 1986 only 36 African American women had graduated from the architecture program at Tuskegee Institute, points out Carla Jackson Bell, professor and current Dean at Tuskegee. The female-free thirty years from the 1930s to the 1960s might be due to traditional gender roles of the time; however, by the 1970s and with the advent of Second Wave Feminism, Black women began to enroll in more consistent and greater numbers. Yearbook photos from this era depict women at these HBCUs as integrated into their classes, pouring over drafting tables and participating in extracurricular activites; staged as these photos might have been (“oh, what a surprise! You caught me here, perfectly posed with a drafting pen in my hand!”), they try to illustrate a dynamic, gender-integrated learning environment.

During that same time period from the 1970s to the 1980s, non-HSBCU architecture programs experienced similar trends of increased female attendance — but Black female enrollment remained very low. At the conference in 1983, Renee Kemp-Rotan, then an architecture instructor at Howard University and today an urbanist, said, "When I was in architecture school at Syracuse University in the early 1970s, I was the only black female there. I didn't think there were any more like me around.” She later said that when she first arrived on campus, she “was asked by students and faculty alike: "What the heck are you doing here?"”

Female and male architecture students gathering in front of a model, 1959. Courtesy of Howard University Yearbook.

While I wish I could say that the numbers are dramatically different today, that isn’t quite the case. Better, yes — that is true: by 2004, Tuskegee had 112 female graduates from the architecture school, including seven of whom earned the master of architecture degree. Numbers have only improved from there, although Black women still make up only about 34% of all Black architecture students in the country. Significantly, though, HBCUs continue to be critical in the education of Black female architects, enrolling about a third of all Black architecture students — despite the fact that there are only seven architecture programs at HBCUs. “This is substantial, because, on average, each of the remaining degree programs only graduates 2 Black architecture students each year,” notes educator Kendall Nicholson (um, wow. Reflecting on my own educational experience, that is precisely the case).

And its not just in the student body at HBCUs where we’ve seen a shift in female representation; it’s also in the faculty and leadership. In 1983, Cook was the only Black female associate dean of architecture in the country; today, there are two out of seven HBCUs with architecture programs: Carla Jackson Bell (dean of Tuskegee’s architecture school, selected in 2016), and Hazel Ruth Edwards, Ph.D., (chair of the Department of Architecture at Howard University beginning in 2019).

So, why do these numbers for both students and faculty matter? For obvious reasons, it’s meaningful to be surrounding by peers who understand your background, can empathize with you, and perhaps even provide advice. As Cynthia Johnson, who was working for the D.C. Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs when she attended the conference in 1983 said, "It's good to know you are not the only one around." And similarly, from the eyes of a student, seeing a Black female academic hold such a high post is equally, if not more, meaningful. Katherine Williams said in an Architect Magazine article in 2021, “As a Howard University alum, I can attest that having professors who looked like me was important and helped me better understand the history of which I was a part.”

Back in 1983, Norma Sklarek commented on the bravery of those in attendance at the conference, stating that they had “dared to enter a field that is controlled and dominated by white males." Daring as it was — and lonely as it often was as well — it is a field that we hope is continuing to evolve, change, and grow.

Resources:Want to read, listen, or learn more? Here’s what we referenced to research this piece:

Dreck Spurlock Wilson. African American Architects : A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945. Routledge, 2004.

Gabriel Kroiz, “The Manifesto Off the Shelf Educating Black Architects at Morgan State University.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) 67, no. 2 (2013): 205–13.

J. Max Bond Center / CUNY, Inclusion in Architecture Report, 2015.

Katherine Williams, How HBCUs Benefit Architects and Architecture. Architect Magazine, October 19, 2021.

Kendall Nicholson, Ed.D. “Where are My People? Black in Architecture.”

Nancy Anita Williams, "Howard Conference A Rallying for Black Female Architects," The Washington Post, 15 December 1983, DC4.

The National Architectural Accrediting Board, Inc., 2014 Report on Architecture Education at Historically Black Colleges and Universities

Oral History with Normal Merrick Sklarek through the National Visionary Project

Pamela Newkirk, Tuskegee, Achimota and the Construction of Black Transcultural Identity.

Pamela Newkirk, “Tuskegee’s Talented Tenth: Reconciling a Legacy.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 51, no. 3 (June 2016): 328–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909615612113.

Paul A. Wellington. Black Built: History and Architecture in the Black Community.

Pioneering Women of American Architecture website

Renee Kemp-Rotan, “Being a Black, Female Architect In a White, Male Profession.” Architecture: the AIA journal Vol. 73 (Feb 1984): 11.

Simone Ruskamp, Department of Architecture: Women and the Making of Howard University

Vinson E. McKenzie, NOMA Historian, President, AAIAH, African American Women in Architecture: A History.